The lack of a coordinated coronavirus strategy for homeless communities could be catastrophic for sick and older people already struggling to survive in tents and overcrowded shelters in California, advocates warned.

Homeless organizations in California, which now has the highest numbers of reported Covid-19 infections along with New York and Washington state, say they lack the resources and government support to effectively stop the virus’ spread in encampments and shelters, and that the shortage of tests and beds could have devastating consequences. California is home to the largest homeless population in the US, with a housing crisis that is already a public health emergency in Los Angeles, the Bay Area and other regions.

“We are not prepared yet for a crisis like this,” said Rev Andy Bales, who runs the Union Rescue Mission (URM) at Skid Row, the epicenter of homelessness in downtown LA. “Individually, we are doing everything we can … but we will be losing precious souls out on the street if we don’t take immediate action.”

The coronavirus death toll in the US was at 26 on Monday, according to Johns Hopkins’ tracker, with more than 700 confirmed cases and significant outbreaks on the west coast. California declared a state of emergency after authorities reported cases in LA, the Silicon Valley region and elsewhere, and on Monday, the Grand Princess cruise ship, which had infected passengers on board, also docked in Oakland, where officials were preparing to move people into quarantine.

There have been no reports yet of cases among California’s homeless populations. That lack of confirmed cases is expected given how sparse the testing has been so far, but advocates are bracing for potential outbreaks as some experts have warned that the US is past the point of containment and must look toward mitigation.

Fear and anxiety has escalated among some homeless communities.

“I ain’t ready to die yet,” said Kevin Wilkerson, a 52-year-old Skid Row resident, who said he was worried about Donald Trump’s flippant response to coronavirus and the fact that the president has pursued funding cuts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This virus is nothing to play with.”

The challenges for the homeless population are severe and complex. Residents without stable housing cannot follow the basic recommendations of self-quarantining when needed, and they can also struggle to access water for handwashing.

“You can tell people to stay home, but the shelters are people’s homes and it’s a dangerous place to be,” said Eve Garrow, the homelessness policy analyst with the ACLU of Southern California. Garrow has researched the unsanitary, unsafe and crowded conditions inside the state’s shelters. “We have many older adults with compromised immune systems living in the shelters, sharing living spaces, restrooms, showers and eating areas. It’s almost impossible to think this wouldn’t create a reservoir for the transmission of highly infectious viruses.”

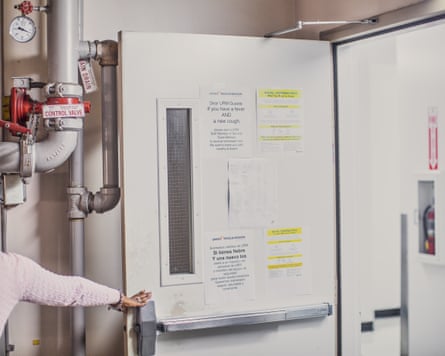

At the URM at Skid Row, which has beds for roughly 1,000 people, Bales said he has installed new hot-water handwashing stations and ordered protective equipment. The not-for-profit is also prepared to quarantine coronavirus patients in a gym in the building, and has put up signs telling people to report to staff if they have a fever and cough, ensuring them they will have a place to stay if sick. “Can you imagine people suffering on the streets alone? We can’t bear that thought.”

But because there is a national shortage of coronavirus test kits, URM does not expect it will be able to test any residents in the near future. Health authorities have told Bales to prepare to quarantine people without tests, since the kits would first go to hospitals, care homes and other organizations once they are available: “We are last on the list to receive the tests, even though we are the most vulnerable.”

That means the URM will treat anyone with a fever and cough as a coronavirus patient. Health officials have also advised the organization to send residents to the emergency room only in the most severe cases, Bales said: “We cannot take someone to the hospital unless they are at the point of struggling to breathe.” Chronic lung disease is common among URM residents.

‘The shelters could be a death sentence’

In LA county, where 44,000 people live unsheltered in cars, tents and makeshift quarters, an average of nearly three homeless people die each day. That rate could climb, warned Stephen “Cue” Jn-Marie, a Skid Row pastor: “The shelters can be a death sentence because people are so close in proximity.”

On Monday, San Francisco officials announced a $5m emergency fund to protect the homeless from coronavirus, which will go toward expanded cleaning in shelters and single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels, extended shelter hours and meal options, and an enhanced food delivery program for elderly SRO residents who are staying inside to protect themselves.

But Jennifer Friedenbach, the director for the Coalition on Homelessness in San Francisco, said people needed immediate safe housing – not emergency shelters with high exposure risk: “The federal government created this crisis of thousands of people living outdoors who don’t have access to water. Decades of immoral inaction have set us up for this complete catastrophe.”

Friedenbach also said the city should stop all sweeps of homeless encampments so that people living on the street don’t lose their medications and other belongings, and don’t lose contact with outreach workers, which could make it harder for them to get medical help.

Garrow, of the ACLU, noted that emergency shelters are largely unregulated, and argued that the state should immediately adopt standards for how they prevent and respond to coronavirus outbreaks and implement a system to ensure compliance. “The system is dire,” she said, adding that she heard from one southern California shelter resident that a site had recently left its soap dispensers empty. She noted that people sometimes have no other options, since police will cite or jail them when they sleep outside and decline to go to a shelter.

A spokesperson for the California Department of Public Health did not respond to questions about safety within emergency shelters, saying in an email that people “experiencing homelessness are not likely to have any particular risk for [coronavirus] related to international travel or exposure to recent travelers”. LA health officials did not respond to questions about shelters.

Wendy Parmet, a Northeastern University law professor and health policy expert, said she was concerned that there appeared to be little discussion at the national level about homelessness. She said she was particularly worried that shelters would end up adopting overly broad or restrictive quarantines that could unintentionally result in increased transmission. “People who are homeless have higher rates of all kinds of health challenges. It’s very scary.”

At Skid Row on a recent afternoon, some residents said they were starting to get more afraid.

“They should have somewhere we can get tested,” said Yolanda Green, 56, who has been living at the Downtown Women’s Center for over a year. She noted that some people have the flu or a cold, and it’s hard to know if they could have coronavirus. “I keep washing my hands for 20 seconds, using hand sanitizer. I’m staying away from people, but it’s hard. I don’t want to catch it.”

Rocio Martinez, 51-year-old URM resident, said she always washes her hands and hasn’t changed her routine – and that it didn’t seem others had, either. “I don’t see anybody covering their mouth or cleaning themselves extra, even though there are a lot of flyers around saying to do that.”

She said she wasn’t personally worried and noted that residents living on the streets and in shelters have already overcome so many threats to their health: “People here are very resilient.”