The Suburban Backlash Against the GOP Is Growing

Donald Trump’s strategy of revving up his rural base may not be worth the cost.

The shift of metro areas away from the Republican Party under President Donald Trump rumbled on in yesterday’s elections, threatening the fundamental calculation of his 2020 reelection plan.

Amid all the various local factors that shaped GOP losses—from Kentucky to Virginia, from suburban Philadelphia to Wichita, Kansas—the clearest pattern was a continuing erosion of the party’s position in the largest metropolitan areas. Across the highest-profile races, Democrats benefited from two trends favoring them in metro areas: high turnout in urban cores that have long been the party’s strongholds, and improved performance in white-collar suburban areas that previously leaned Republican.

“When Trump was elected, there was an initial rejection of him in the suburbs,” says Jesse Ferguson, a Virginia-based Democratic strategist. “We are now seeing a full-on realignment.”

In that way, the GOP’s losses again raised the stakes for Republicans heading into 2020. In both message and agenda, Trump has reoriented the Republican Party toward the priorities and grievances of non-college-educated, evangelical, and nonurban white voters. His campaign has already signaled that it will focus its 2020 efforts primarily on turning out more working-class and rural white voters who did not participate in 2016.

But yesterday’s results again suggested that the costs of that intensely polarizing strategy may exceed the benefits. Republicans again suffered resounding repudiations in urban centers and inner suburbs, which contain many of the nonwhite, young-adult, and white-collar white voters who polls show are most resistant to Trump. If the metropolitan movement away from the Trump-era GOP “is permanent, there’s not much of a path for Republican victories nationally,” former Representative Tom Davis of Virginia, who chaired the National Republican Congressional Committee about two decades ago, told me.

Some in both parties see the results as more confirmation of the pattern from the 2018 midterm elections, when Democrats won a majority in the House of Representatives: Trump’s effort to mobilize his nonurban base around white identity politics is having the offsetting effect of turbocharging Democratic turnout in metropolitan areas, which are growing faster than Trump’s rural strongholds.

“The Trump campaign has focused on a singular strategy of looking for more voters who look like the type of voters who already like him, rather than trying to persuade anyone else,” says Josh Schwerin, senior adviser at Priorities USA, a Democratic super PAC that spent heavily in the Virginia races. “But the issues they are using to motivate those potential voters create a backlash for voters in metro areas who don’t like Trump.”

Unique local conditions contributed to each of yesterday’s most disappointing results for Republicans. In Virginia, Democrats benefited from a court-mandated redistricting of some state legislative districts after the initial lines drawn by the Republican-controlled legislature in 2011 were deemed discriminatory against minorities. The new maps substantially increased the African American share of the electorate in four of the six state House seats that Democrats appear to have captured, according to data collected by the Virginia Public Access Project. Huge spending by outside groups focused on gun control, gay rights, and legal abortion also boosted Democrats there.

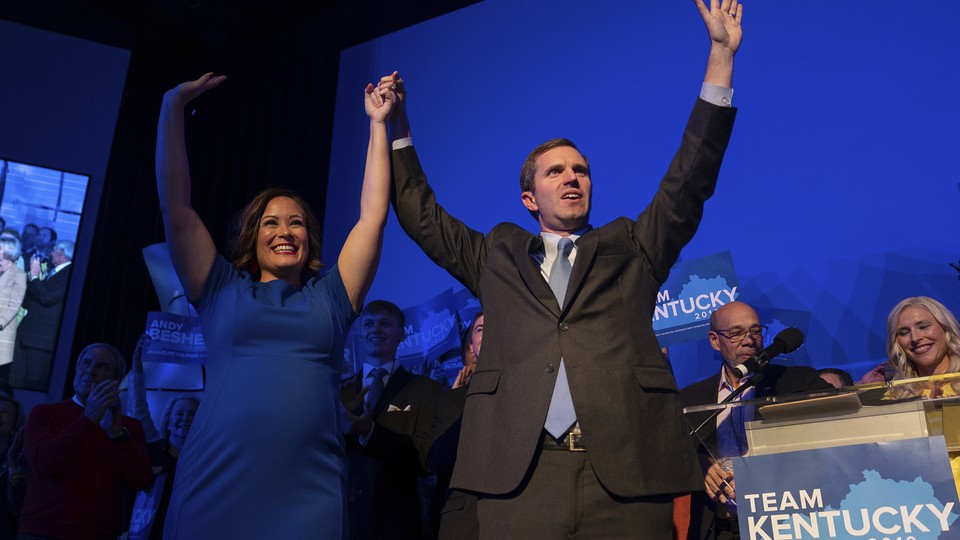

In Kentucky, the Democrat Andy Beshear appeared to oust incumbent Republican Governor Matt Bevin, though the Associated Press still has yet to declare him the winner and Bevin has indicated he may contest the result. Bevin, a belligerent figure, was among the country’s most unpopular governors, and he provoked a fierce organizing effort against him by teachers and organized labor. “By all accounts, this was the best get-out-the-vote effort ever mounted in Kentucky by the Democrats … driven by the teachers and the labor unions,” says Al Cross, the director of the Institute for Rural Journalism at the University of Kentucky. Bevin also appeared to suffer in rural areas from his drive to pull back the state’s Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. And even as Bevin apparently was defeated, Kentucky Republicans posted solid wins in the other statewide elections.

But looming over all these local factors was the consistency of the metropolitan movement away from the GOP. Not only in urban centers, but also in suburban and even some exurban communities, Democrats reaped a double benefit: They increased their share of the vote even as turnout surged.

The combination produced some astounding results in Kentucky. Beshear won the state’s two largest counties—Jefferson (which includes Louisville) and Fayette (which includes Lexington)—by a combined 135,000 votes, according to preliminary results. That was nearly triple the total vote advantage that Jack Conway, the Democrats’ 2015 nominee against Bevin, generated in those two counties. Beshear in fact won almost exactly as many votes as Hillary Clinton did in Jefferson County and slightly more than she did in Fayette—an incredible achievement given how much lower turnout usually is for a governor’s race in an off year. “That’s insane. It is incredible. It cannot be stressed enough,” says Rachel Bitecofer, a political scientist at Christopher Newport University, in Virginia.

The legislative elections in Virginia show the same pattern of the suburban erosion for the GOP in the Trump era. Democrats overthrew narrow Republican majorities in both chambers of the General Assembly by capturing at least five state House seats (while leading narrowly in a sixth) and two in the state Senate. They included seats in the Washington, D.C., suburbs of Northern Virginia and near the state capital of Richmond. For the first time in 50 years, Democrats now control all of the state House seats in Fairfax County, which is near Washington, D.C.

But those new gains were probably less telling than what didn’t change: Democrats didn’t lose any of the previously Republican seats that they captured in suburban areas—particularly Northern Virginia and Richmond—in their landslide win in the state in 2017, which foreshadowed Democrats’ gains in the 2018 midterms. “The key is, the Republicans didn’t win back any of the suburban seats they lost,” Davis said. “Basically the mold in those areas hardened. We were like, ‘Oh, it was temporary—a one-time turnout [surge].’ But they didn’t win them back.”

The Democrats’ suburban gains extended down the ballot too. For example, Loudon and Prince William Counties, in the outer Washington suburbs, were once symbols of Republican strength in fast-growing exurbs. Yesterday, Democrats flipped control of the county commissions in both of them.

A similar pattern unfolded in the suburbs of Philadelphia, where Democrats captured a majority in three different counties’ boards and defended their majority in a fourth; the area is likely crucial to the party’s 2020 prospects in Pennsylvania.

Republicans pointed to some good news: The party held the governor’s mansion in Mississippi, ousted a Democrat in a New Jersey state House seat that Trump won in 2016, and elected an African American Republican attorney general in Kentucky. They avoided the worst-case scenario in Virginia by holding close four state Senate seats where Democrats reached about 48 percent of the vote or more. But the bottom line across all the results is clear. As Davis starkly put it, “This was not a good night for the Republican Party.”

John Weaver, a veteran Republican political strategist who has been critical of Trump, says that while Republicans can “cherry-pick” local factors behind each of their losses, the cumulative pattern of suburban erosion for the party is unmistakable. “We are not talking about a gradual change,” he says. “We are talking about dramatic overnight flips from what used to be reliably Republican to now reliably Democrat. And the turnout is massive.”

Though Bevin suffered some erosion in rural eastern counties in the state, the GOP generally held its ground in such areas, both in Kentucky and Virginia. That widening separation between the GOP’s strength outside of metro areas and an intensifying tilt toward Democrats inside of them continues the underlying pattern of geographic polarization that has defined politics in the Trump era.

In 2016, Trump lost 87 of the 100 largest U.S. counties by a combined 15 million votes, but then won over 2,600 of the remaining 3,000 counties, the most for any presidential nominee in either party since Ronald Reagan in 1984. In 2018, Republicans suffered sweeping congressional losses across urban and suburban America, but avoided hardly any congressional losses in heavily rural districts. While big showings in diverse metro areas helped Democrats win Republican-held Senate seats in Arizona and Nevada, Republicans snatched three Senate seats from Democrats in states with large rural white populations: North Dakota, Missouri, and Indiana.

Rather than looking to court urban areas, Trump has more frequently denounced places such as Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles in an attempt to energize his mostly nonurban base. He continues to aim his message preponderantly at culturally conservative whites, and his campaign has signaled that it considers increasing turnout among such voters central to his reelection hopes.

Few in either party dispute that such a strategy could allow Trump to squeeze out another Electoral College victory, even if he loses the popular vote; he could do so by holding a narrow advantage in a few closely contested states, from Florida, North Carolina, and Arizona in the Sun Belt to Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan in the Rust Belt.

But yesterday’s results underscore how narrow a wire the president is walking with that strategy. Even taking into account Bevin’s personal unpopularity, Bitecofer says the Kentucky result should caution Republicans about a plan that accepts metropolitan losses to maximize rural and small-town gains. “If it can’t work in Kentucky … you cannot do it in Wisconsin or Michigan,” she says. Beyond Trump, the urban/nonurban divisions evident in this week’s elections “should scare the ever-loving bejesus” out of 2020 Republican Senate candidates in states with large metropolitan populations, including Arizona, Colorado, and North Carolina. “Their danger level … has increased exponentially,” she argues.

Another GOP strategist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal party strategy, took a similar, if less severe, lesson from the results. In 2016, the strategist noted, Trump benefited not only because rural and non-college-educated white voters turned out in big numbers, but because turnout was weak among minorities and mediocre among young people. But in 2018—and again last night—large turnout in metropolitan areas swamped strong showings for the GOP in rural communities, the strategist noted. That raises the question of whether even big turnout in nonmetro areas will suffice for Trump if the metropolitan areas moving away from him continue to vote at the elevated levels evident in 2018 and 2019.

Trump can’t bank on a 2016 redux: “Clearly that isn’t going to happen this time,” the strategist told me.

Davis, the former NRCC chair, likewise believes that the GOP’s transformation from a party of “the country club to the country” does not add up to long-term success. “What’s happening is that the fast-growing areas [are] where the Democrats are doing better,” he told me. “There aren’t enough white rural voters to make up the difference.” In 2020, he said, “the silver lining” could be if Democrats nominate an extremely liberal presidential candidate, such as Senators Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, who could leave anti-Trump suburban voters “conflicted.” But, given the intensity of the suburban backlash to Trump, he said, even that is no guarantee that those voters will rebound to him.

Such words of warning have been extremely rare among Republicans: Despite the GOP’s recent metropolitan losses, Trump’s approach has generated astonishingly little dissent inside the party. Yesterday’s results are unlikely to break that silence. But Weaver, like other GOP strategists dubious of Trump, says the party cannot indefinitely ignore the implications of prioritizing rural strength at the price of losing ground in the urban centers, which more and more are driving the nation’s economic innovation and its growth in population and jobs.

“Politics is a free-market enterprise. You have to sell a product,” Weaver says. “And Republicans are going to find themselves, by their own decision making, eliminated as an option for many, many voters, many, many demographic groups for generations to come.”