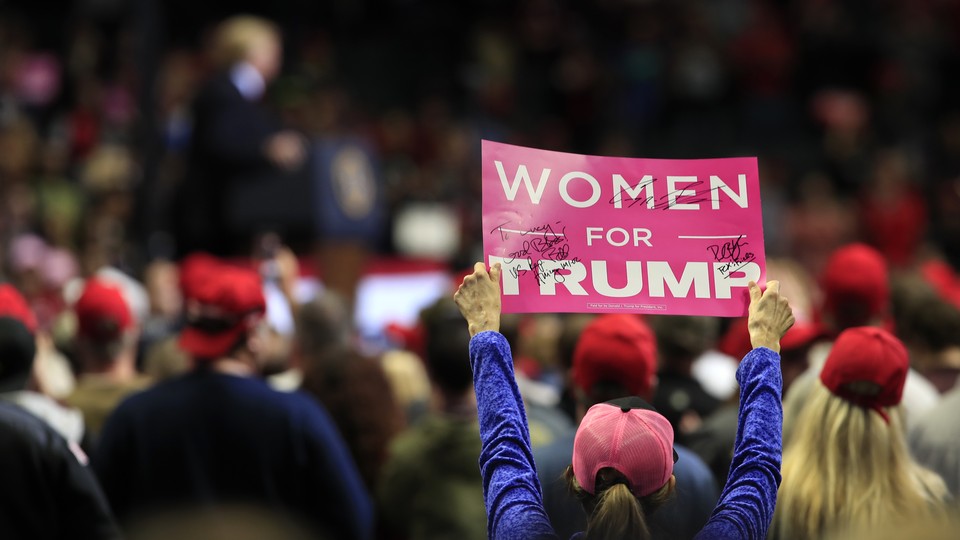

Will Trump’s Racist Attacks Help Him? Ask Blue-Collar White Women.

His strategy rests on a bet: that these voters will respond just as enthusiastically to his belligerence as working-class white men.

Donald Trump’s turn toward more overt racism in his “go back” attacks on four Democratic congresswomen of color rests on an unspoken bet: that the women who are part of his core constituencies will respond to his acrimony as enthusiastically as the men.

But polling throughout Trump’s presidency has indicated that his belligerent and divisive style raises more concern among women voters than men in one of his most important cohorts: the white working class. And a new set of focus groups in small-town and rural communities offers fresh evidence that the gender gap over Trump within this bloc is hardening.

In the Rust Belt states that tipped the 2016 election to Trump—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin—few things may matter more than whether Democrats can fan doubts about Trump that have surfaced among blue-collar white women or whether the president can rebuild his margins among them with his polarizing racial and ideological attacks.

“The white working-class men look like they are approaching the 2016 margins for Trump, but not the women,” says the veteran Democratic pollster Stanley Greenberg, in a judgment supported by public polling. “Clearly the women are in a different place.” Greenberg conducted the focus groups, whose findings were released today, for the American Federation of Teachers.

In both parties, most strategists I’ve spoken with agree that Trump’s bellicose attacks on the congresswomen will harden the opposition he faces among the groups most accepting of America’s changing identity: young people, minorities, and college-educated white voters, especially women. What’s more, his new offensive represents exactly the sort of behavior that has led an unprecedented number of voters satisfied with the economy to nonetheless express doubts about his leadership: In an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist College poll released earlier this week, fully one-third of adults who said the economy is working for them personally still said they disapprove of Trump’s job performance. An equal share of these voters said they now intend to vote against him for reelection. To offset that unusual defection among the economically content, Trump must maximize his margins—and turnout—among the groups that have been most receptive to his exclusionary racist and cultural messages: older, nonurban, evangelical-Christian, and non-college-educated white voters.

Democratic strategists generally believe that Trump’s rhetoric will likely cost him more than it gains him in the total popular vote. But the past week has produced a collective spasm of anxiety in Democratic circles that his new attacks could nevertheless help him win a second term because the working-class whites believed to be most receptive are overrepresented in the three most crucial states: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and, above all, Wisconsin. (In the last state, non-college-educated whites cast fully three-fifths of all votes in 2018, according to the Census Bureau, more than in any other swing state.)

But Trump’s strategy faces a huge obstacle if working-class women don’t buy in to his message as much as working-class men. That’s for a simple reason: Every data source—from the exit polls to the Pew Research Center’s analysis of voter files to studies by Catalist, a Democratic voter-targeting firm—shows that these women reliably cast slightly more than half of all the votes from the white working class.

“If you think about the strategy they had in ’16 … where he campaigned and went into these [blue-collar and nonmetropolitan] areas and really drove up the vote—that doesn’t work if the women aren’t responding to it, if they watch him and they get put off by it,” Greenberg says. “It only works if women are part of the story. You just can’t get the numbers if half of white working-class, nonmetro voters are put off by what you are doing.”

White working-class women have been a reliably Republican-leaning constituency for the past generation. Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996 is the only Democratic presidential candidate since 1980 who has carried them. Data measuring the 2016 vote show that Trump expanded the GOP margins with these women to the highest level in years: His advantage ranged from 21 percentage points, according to calculations by Catalist; to 23 points, according to Pew; to 27 points, according to the exit polls.

But in 2018, Republicans sagged among these women. Nationally, GOP House candidates still won their vote overall, but by less robust margins than Trump did two years before: 14 points per the exit polls and 17 percent per the Catalist calculations. And Democrats in 2018 generally performed much better with these voters in marquee Senate and governor’s contests in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. (Only in the Senate race in Michigan and in the governor’s race in Wisconsin did Republicans retain a solid lead with these voters.)

Trump’s job-approval rating on Election Day 2018 among these women stood at just more than 50 percent in all three states, according to detailed results provided to me by Edison Research, which conducts exit polls for a consortium of media organizations. In each state, that represented a decline of about five percentage points from his share of their vote in the presidential election. That’s not a radical shift, but in three states that were decided by a combined 78,000 votes in 2016, it could have a powerful impact.

National polls since the 2018 election have continued to show Trump facing a cooling reception from these women. Both the latest NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, released early last week, and the NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll released this week show him with a net-positive approval rating of just seven percentage points among blue-collar women, well below his vote advantage in 2016. The Marist poll found them divided almost exactly evenly on whether they intend to vote for or against Trump for reelection. That’s a much more tenuous equation than Trump faces among blue-collar white men. Both of the latest national surveys from NBC/Wall Street Journal and Marist found that the share of those men who approve of his performance still stands about 30 percentage points higher than the number who disapprove.

The new focus groups Greenberg led help illuminate this gender divide. The sessions were conducted in nonmetropolitan areas in Nevada, Maine, and Wisconsin among white working-class voters, both independents and loosely identified Republicans, who mostly supported Trump in 2016. In the groups, Greenberg found that Trump still receives good marks from working-class white men. They credit him for a strong economy, see his confrontations with China and other trading partners as standing up for America, and respond viscerally to his hard-line agenda and rhetoric across a wide array of issues relating to immigration.

“The men were far more likely to agree with Trump on what they read and heard, and unlike the women, they almost all thought the [border] wall was a good idea or at least a net positive,” Greenberg and his colleague Chad Arthur wrote in a memo accompanying their findings. “They were more likely to agree with Trump on illegal immigrants bringing drugs and crime across the border.”

The women weren’t immune to Trump’s arguments on immigration. In the groups, many agreed with him on two fronts: that there is a crisis at the southern border, and that undocumented immigrants represent an economic threat because they are “willing to work for peanuts,” as one woman put it.

But among the women, those areas of agreement were mitigated by other concerns about Trump, including their belief that, on immigration, “his rhetoric … made him sound ‘racist’ or ‘ignorant,’” as the report notes. “There were a lot of mentions of intolerance in reaction to what he was saying and doing,” Greenberg says.

That recoil represents one component of the broader unease these women expressed about the level of acrimony and division under Trump. While the men almost entirely found ways to justify Trump, the women expressed much more discomfort about the way he talks about race-related issues, his overall style, and whether he respects women. “The women are not making excuses for him,” says Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, which commissioned the research. “What you’re seeing is a big difference between decency and bombast. And these women are saying, ‘This guy is bombastic; he’s disrespectful.’”

Women were also more likely than men in the groups to say that Trump’s economy hasn’t delivered improvement for their family, and they were more likely to cite rising health-care and prescription-drug costs as an especially acute squeeze. In both parties, strategists I’ve talked with agree that Democratic promises to defend the Affordable Care Act, particularly its provisions safeguarding patients with preexisting conditions, were crucial to the party’s recovery among blue-collar white women in 2018.

Summarizing these views, Greenberg concluded that while working-class white men look very tough for Democrats to win over next year, the party has an opportunity to consolidate its modest 2018 revival among their female counterparts. For many of the women who backed Trump in 2016, he wrote, the president now “is seen as ego-centric and divisive and failing to deliver for working people, particularly the women and particularly on health care.”

Even with these openings, however, Democrats still face significant obstacles. This week’s NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll suggests that non-college-educated white women are essentially just as hostile as working-class white men to vanguard liberal ideas that have emerged in the 2020 Democratic presidential race. Those issues include a single-payer health-care plan that would eliminate private insurance, allowing undocumented immigrants access to any federally funded health-care plan, and decriminalizing unauthorized crossing of the U.S. border. Additionally, while recent polls by the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute show that these women don’t quite match the hostility of the men in their cohort to a wide array of demographic and social changes in the country, a majority agree on several ideas: that the growing number of immigrants threatens traditional American values, that the U.S. way of life must be protected against foreign influence, and that white people face as much discrimination as black people. All of those attitudes correlate with support for Trump.

Still, Greenberg’s research, like the other public polling, suggests that Trump is in something of a political box with working-class white women. He can activate their cultural and racial anxieties with more attacks of the kind he’s directed against the so-called squad of liberal Democratic congresswomen. But in the process, he’s likely to also intensify their concerns about his divisiveness and perceived “bullying.” After playing video clips of Trump’s salvos against immigrants and “socialists” to the women in his focus groups, Greenberg says he flatly does not believe that Trump’s heightened racial and ideological attacks will work with them: “I came away utterly unafraid of him playing the immigration card in its most extreme form.” (Weingarten echoed that judgment.)

They may be among the few Democrats that sanguine as Trump moves to polarize the electorate around questions of racial resentment and American identity more fiercely than any national figure since George Wallace. How these blue-collar women respond to Trump’s more explicit appeals to white racial identity will be pivotal in determining whether that optimism is justified.