The Sinister Logic of Trump’s Immigration Freeze

The White House is closing pathways to citizenship while maintaining a flow of exploitable immigrant labor.

More than a decade before he became Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate, the Texas Democrat John Nance Garner tried to convince the biggest immigrant hater in Congress that his state desperately needed Mexican labor.

“I do not mean to say by that, Mr. Chairman, that the character of the people that would come in under this resolution are particularly desirable citizens; I won’t make that statement,” Garner told the Washington Republican Albert Johnson, testifying before the immigration committee in 1920. “But I do make this statement: that the people that would come in under this resolution—in my opinion, 80 percent of them will return to Mexico. They do not know anything about government. They come over here to get a little money and go back to Mexico because they would rather live there.”

Garner understood his audience. Johnson, whose rise to power involved both crushing labor unions and railing against Asian immigration, was most worried about preserving the political hegemony of Americans he considered white. A minority perspective in the hearing, represented by the Texan entrepreneur Clark Pease, was that Mexicans make “just as good citizens” as anyone else.

“The trouble is that you ask for them only for one year, and you know you will want them back again in another year,” Johnson said, addressing those who had testified that Mexican immigration would be a boon to the United States. “You fail to look to the future. You forget that the South never realized 100 years ago that the Negro would sit in the legislatures. The citizens of those states never thought it could happen, but it did.”

Garner likely agreed with Johnson on that point, having supported post-Reconstruction efforts to disenfranchise black voters in Texas. Neither man wanted to see Mexican laborers stay in Texas and become American citizens, but Texas’s commercial interest in cheap labor was too great for Garner to support measures to further restrict Mexican immigration.

A few short years later, Johnson would successfully sponsor the most significant immigration-restriction bill in American history, designed to keep out those whom nativists saw as genetic undesirables, including Asians and Africans, Jews and Italians. But diplomatic considerations and commercial interests would prevent Johnson from imposing similar restrictions on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, setting up the conflicts that have defined the U.S. immigration debate for the past century.

The two impulses—on the one side, an economic demand for cheap labor; on the other, a desire to preserve white political hegemony—appear to be opposite poles in the immigration debate. But by preserving wealthy Americans’ access to exploitable labor while preventing the laborers themselves from earning the benefits and rights that come with American citizenship, the two visions can be reconciled. Donald Trump’s recent executive order on immigration is constructed to do precisely that.

“The nativist right wants a moratorium, meaning an end to all legal immigration. They say it’s about numbers, but it’s about race,” Frank Sharry, the head of the immigration advocacy group America’s Voice, told me. “But Trump wants to run on culture wars and economic comeback, so he’s very solicitous of business demands. And the prospect of a ‘ban’ that ends the flow of workers to the fields, the hospitals, and the research institutions drew very strong opposition.”

Last week, Trump announced bombastically on Twitter that he would be “signing an Executive Order to temporarily suspend immigration into the United States,” citing “the need to protect the jobs of our GREAT American Citizens.”

Nativists frequently present their arguments as defenses of workers, particularly low-wage workers. More than 22 million Americans have lost their jobs and 50,000 Americans have lost their life due to the coronavirus, and Trump likely saw an opportunity to divert attention from his mishandling of the outbreak to immigration, terrain on which he is far more comfortable fighting.

The actual policy, however, is much more modest than advertised.

“He’s delayed green cards for some family-reunion cases and some employers, but it’s far from a ban,” Sharry said. “Families and refugees, no. Workers, yes—but only if the workers are on temporary visas so we can extract their labor without extending full citizenship and rights to them. It says we want expendable workers we can exploit, not new Americans who demand equality.”

The order does not shut off the spigot of temporary guest workers at all—rather, it prevents thousands of people applying for U.S. citizenship from abroad from acquiring green cards. It does not prevent the wealthy from exploiting temporary foreign workers whose legal status and employment can be used as leverage to keep wages low or stifle unionization. But it does block thousands of immigrants who were on the verge of obtaining the rights and privileges of American citizenship from coming to the United States and settling permanently. At the same time, it preserves the EB-5 immigrant investor program, which effectively allows wealthy foreigners to purchase green cards.

“What this did instead was just mostly cut the number of people who can come to reunify with family, and including the … parents of adult U.S. citizens,” says Daniel Costa, an analyst with the Economic Policy Institute. Trump has “taken action to reduce the ways that immigrants can come to the U.S. where they have rights and a path to permanent residence and citizenship, but he hasn’t touched the visa categories where there’s tons of abuses.” Indeed, Trump has increased access to low-wage immigrant labor every year he has been in office, while sharply restricting the avenues available to immigrants for acquiring American citizenship.

Business interests want to maintain access to exploitable low-wage labor, including both undocumented immigrants and guest worker visas. Nativists want to maintain America’s traditional racial hiearachy, which is endangered less by a captive, temporary labor force, than by non-white immigrants who settle in America permanently. The result is an immigration “ban” that targets immigrants who may become American citizens, but preserves the guest-worker programs nativists claim lock out American workers. The last thing either side wants is, as Johnson put it, for immigrant workers to be able to sit in legislatures.

The president’s policy, therefore, fails under its own premise of shielding American workers from foreign competition. What neither the nativists nor their partners in the corporate elite can support is a scenario in which low-wage immigrant workers can access the rights of American citizenship to build political power. According to The New York Times, Trump “backed away from plans to suspend guest worker programs after business groups exploded in anger at the threat of losing access to foreign labor.”

The Trump administration is a coalition forged between those ideologically committed to maintaining an aristocracy of wealth and those committed to restoring an aristocracy of race. Preventing prospective immigrants from becoming citizens while maintaining the flow of exploitable immigrant labor to those who depend on it fulfills both aspirations. In keeping with Trump’s authoritarian instincts, the executive order does so without Congress’s approval, instead relying, as prior decrees have, on a putatively temporary measure that can be renewed indefinitely if the administration so chooses. Earlier immigration restrictionists sought to pass their ideas into law; the Trump administration is content to issue executive orders, counting on pliant courts packed with right-wing judges to either sanction its legislating from the executive branch or plead with false restraint that interfering is beyond the mandate of the court. Although the new restrictions affect relatively few people at the moment, they will hurt many more if the ban is renewed indefinitely.

“If you look at the history of what they’ve done with the Muslim ban or with several other temporary measures, they renewed them as a matter of course. They’ve recently expanded the Muslim ban to add a set of African countries,” says Omar Jadwat, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union. “It’s very much part of their playbook … They’ll go into court and say, ‘It’s a temporary measure. Who knows if in 60 days we’re going to continue?’”

Chief Justice John Roberts, now considered the conservative-dominated Supreme Court’s most likely swing vote, has sanctioned such bad-faith arguments before, most notably in Trump v. Hawaii, the case involving the temporary travel ban that has now been in force for more than three years. But he has also rejected them, such as in Department of Commerce v. New York, in which the Trump administration sought to use the census to enhance the power of white voters at minority voters’ expense, under the transparently false pretext that it was seeking to enforce the Voting Rights Act.

“Very frequently, this administration is asking the court to accept arguments that can realistically be described as bad arguments. And at the end of the day in the census case, they didn’t. In the Muslim-ban case, they did,” Jadwat said. The lingering question, he added, is, “To what degree are the courts going to participate in a farce and pretend that there’s not a substantial likelihood that the administration intends to continue?”

The nativists in the Trump administration, those who see nonwhite immigrants as an existential threat, will hardly content themselves with the narrow focus of the current executive order. The White House aide Stephen Miller falsely bragged to nativist groups on a recent conference call that the executive order had turned off “the faucet of new immigrant labor.”

While the business interests seeking to maintain their guest-worker programs even as Trump shuts off avenues to citizenship resemble the Texan Garner, Miller is the ideological descendant of Johnson. In emails with the former Breitbart News writer Katie McHugh, which she later shared with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Miller praised Calvin Coolidge for signing off on Johnson’s racist and anti-Semitic immigration restrictions, while characterizing their repeal as ruinous and tragic. Miller praised McHugh for a piece lamenting that, as a result of the 1965 law repealing racist restrictions on immigration, “Hispanics will see their number grow by the tens of millions and native-born whites are the only group expected to decline in both absolute numbers and fertility rates,” saying that McHugh was “the only writer in the country who published a piece even mentioning the law and what it did.”

On Fox News nightly, Republican voters are fed a slightly diluted version of this message, warned that liberals, in the words of the host Laura Ingraham, “want to replace you, the American voters, with newly amnestied citizens and an ever-increasing number of chain migrants.” The logic that immigrants’ political beliefs are both inimical to American ideals and genetically encoded also echoes Johnson, who wrote that “our capacity to maintain our cherished institutions stands diluted by a stream of alien blood, with all its inherited misconceptions respecting the relationships of the governing power to the governed.”

Trump is less learned than Johnson, but shares his ideological premises. Just as Johnson’s restrictions allowed immigration from Northern Europe on the grounds that such “Nordic” stock was the basis of American greatness, Trump has complained about immigration from Latin American and African countries he described as “shitholes,” while suggesting the U.S. take more immigrants from Norway. The once-dominant Republican view, represented by Pease, who joked in 1920 that Texas needed “more Mexicans and less Democrats,” is now heretical.

Although the coronavirus outbreak has largely halted immigration to the United States, the pandemic will someday subside, while nativist efforts to engineer a white majority by fiat will not. The long-term objective of those who crafted the president’s executive order is not to protect American workers, or to serve American business interests, or to grow the American economy. It is to maintain America’s traditional aristocracy of race, by any means necessary.

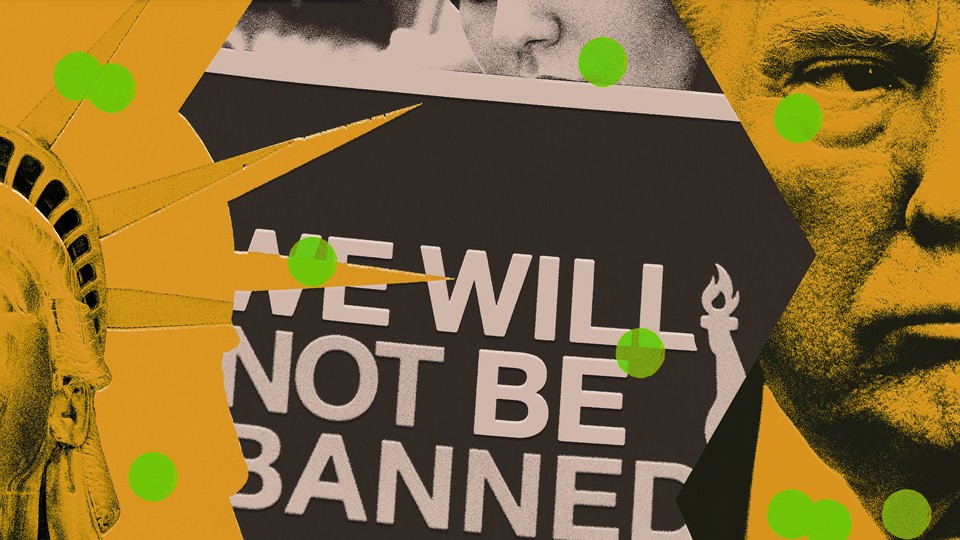

*Photographs by Mark Wilson / Doug Mills / New York Times / Bloomberg / Getty