Less than 72 hours before polls opened in Wisconsin on 7 April, the state legislature convened to weigh an emergency request from the governor, Tony Evers. With Covid-19 cases in the thousands, Evers implored the lawmakers to delay in-person voting for the state’s presidential primary and mail a ballot to every voter in the state.

It was a meeting only in name. Republicans, who control 63 of 99 seats in the state assembly, sent just one member. He brought the session to order and then immediately ended it without taking up the governor’s request. It took just 17 seconds. In the Republican-controlled state senate, the same thing happened, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. It took even less time.

The legislature’s defiance was a naked display of unabashed power – an elected body refusing its governor’s request and turning its back on its constituents in a time of crisis.

The Republican lawmakers who didn’t even bother to show up for the emergency session on Saturday knew that their re-election was guaranteed because of a successful party effort over the last 10 years to entrench themselves in power. Even in a state at the center of some of the most hard-nosed fights over voting, it was a stunning series of events.

That assault on democracy began in 2011, when Republicans drew new lines for political districts in Wisconsin. It was part of a national Republican effort, called Project Redmap, to capture state legislatures and, with those victories, to gain control over redrawing the lines of each district. The goal of Redmap was to conjure districts that would advantage Republicans and disadvantage Democrats – a process called gerrymandering. The writer and author David Daley called Project Redmap “the most audacious political heist of modern times”.

Karl Rove, former senior adviser to George W Bush announced the redistricting effort in the Wall Street Journal, claiming, rightly, that whoever controls redistricting also controls Congress. Later, according to the New Yorker, when Rove addressed potential funders of Redmap in Dallas, he said “People call us a vast rightwing conspiracy. But we’re really a half-assed rightwing conspiracy. Now it’s time to get serious.”

For $1.1m – a small sum in campaign dollars – Republicans won the state legislature and went on to curb Democratic power by passing a strict voter ID law, making it harder for minorities and students to vote, and later stripped statewide elected officials of some of their authority.

“I don’t think many people who are aware of what’s going on, and are tuned into politics and government in this state, would say that it’s anything even resembling a democracy,” said Jay Heck, the executive director of the Wisconsin chapter of Common Cause, a government watchdog group.

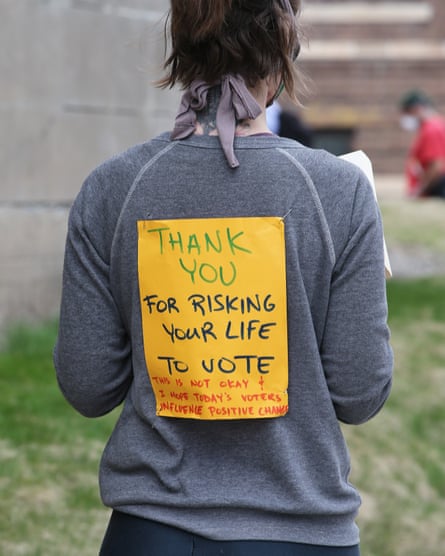

On Tuesday, voters risked their lives to go to the polls, waiting hours in line in Milwaukee. So far, turnout looks like it will be a fraction of what it was in 2016, and that is believed to benefit Republicans, who were seeking to maintain control of a seat on the conservative-leaning state supreme court. It was the state supreme court who voted along partisan lines to overrule Evers’ last-minute effort and to allow the election to move forward.

Wisconsin had long held a reputation as a bipartisan state, and there had been fights over redistricting before. But in 2011, Republicans took it to a new level. They deployed mapmakers to the offices of a law firm across from the state capitol, where they drew different options for maps that tested how much of an advantage could be gained in districts. They closely regulated who had access to the room where maps were drawn, even requiring Republican lawmakers to sign agreements to keep discussions about the maps secret.

Republicans understood that they were drawing maps to maintain power far beyond that year. “The maps we pass will determine who’s here 10 years from now,” one memo at the time read. One assembly district belonging to Andy Jorgensen, a Democrat in the state general assembly, was cracked into four different Republican-friendly districts, Daley wrote in Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count.

The plan worked almost exactly as the mapmakers predicted. In 2012, the first election with the new map in place, Republicans won less than half the votes, but conquered 60 of the state’s 99 assembly seats. The Republicans grew their majority in 2014 and 2016, despite earning just over 50% of the statewide vote.

“It seems impervious to what happens with voters,” said Barry Burden, director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “It really looks like an unresponsive institution.”

Michael Li, a voting rights expert at the non-partisan Brennan Center at NYU, wrote this week: “Wisconsin’s maps are so gerrymandered that Republicans can win close to a supermajority of house seats with a minority of the vote.

“Republicans could act brazenly without fear of electoral blowback because gerrymandered maps make it virtually impossible for them to ever lose their legislative majority,” he wrote. Wisconsin’s maps were crafted with such micro-precision that even if Democrats managed to win a historically high 54% of the two-party vote – a level they’ve reached only once in the last 20 years – Republicans would still end up with a solid nine-seat majority in the state assembly.”

As the gerrymandering project wore on in 2011, Republicans also drafted one of the strictest voter ID laws in the country. It required Wisconsin voters to present a form of photo ID such as a driver’s license or passport to vote. Students could only use their school IDs if they contained a signature and an expiration date.

Despite efforts to block it in court, the law went into effect for the first time in 2016. One study estimated the law could have deterred as many as 23,252 people from voting in Milwaukee and Dane counties, two of the state’s largest, and both Democratic strongholds. Donald Trump won the state by just under 23,000 votes.

Ruth Greenwood, an attorney at the Campaign Legal Center, said the link between voter ID laws and gerrymandering was undeniable. “It definitely all feeds on itself,” she said. “Gerrymandering has meant there are less competitive elections and Republicans know they can maintain the majority. So they continue to restrict the electorate to advantage themselves.”

A few weeks after the 2016 election, Greenwood and a team of lawyers helped convince a three-judge panel to strike down the gerrymandered assembly map, saying it was so severely manipulated that it violated the US constitution. But in 2018, the US supreme court, in a 5-4 vote, overruled the lower court on technical grounds and sent the case back for further review. One year later, it would rule that federal courts could do nothing to stop partisan gerrymandering.

The maps Republicans secretly drew in 2011 laid the foundation for the power they used to force an unprecedented election on Tuesday. Had it not been for gerrymandering, voters in the state might not have had to risk their health to vote, said Nicholas Stephanopoulos, another lawyer who helped challenge the assembly map in federal court.

“If you had fair maps, you would have an evenly divided legislature; you might well have a Democratic legislature, given how well Democrats did in 2018,” he said. “They might have gone along with the governor and agreed to sensible changes in the election schedule and the manner of conducting the election.”

One of the politicians able to consolidate the most power in Wisconsin is Republican Robin Vos, the speaker of the state assembly. In addition to rebuffing Evers’ efforts to postpone the election, Vos blamed Milwaukee officials for warning it wasn’t safe to run Tuesday’s election.

On election day, Vos volunteered at the polls. Speaking to reporters, he again brushed off concerns about holding elections. Dressed head-to-toe in protective equipment, he gave incorrect information about how to request an absentee ballot, before proclaiming it was “perfectly safe to go out”.