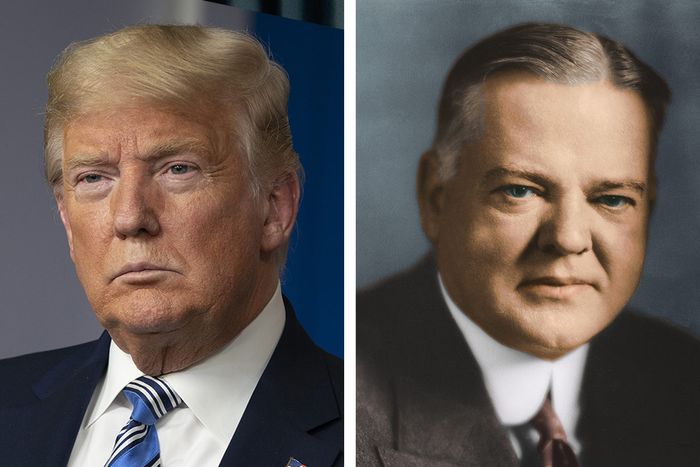

Before the coronavirus pandemic is finally under control, the U.S. economy will undergo its greatest shock since October 1929, when a stock-market crash initiated a Great Depression that lasted a decade. The unemployment rate will likely reach 15 percent by the end of April and could well drift up into the 20s soon after. So it’s natural to speculate as to whether the ignominious political fate of Herbert Hoover, the man who sat in the White House as the Great Depression began, awaits Donald Trump when voters deliver a verdict on his tumultuous presidency in November.

Hoover was elected president by a landslide in 1928, beating Democrat Al Smith by a 58/41 popular-vote margin and losing only six Deep South states. He was defeated by FDR in an almost identically sizable landslide (57/40) four years later, this time winning just six states, all in the northeast. His party proceeded to lose the next four presidential elections, and really didn’t gain any sort of stable parity with Democrats until the 1980s. Hoover’s name was indelibly associated with that legacy of defeat, and Republicans have never quite shaken the reputation for callousness he was thought to have shown as the Depression gripped the country.

The 31st and 45th presidents are similar in a few important ways, beyond a common Republican Party membership. They are the only presidents never to have served in any elected office or in military leadership. They both possessed great personal wealth before becoming president. They both held themselves in high esteem, and were known for stubbornly rejecting sound advice.

The two men also differed significantly in more obvious respects. Hoover was the consummate self-made man; he was orphaned at the age of 11 and performed a host of mentally and physically demanding jobs before he found his destiny as a mining engineer. Trump was the classic silver-spoon scion, and never distinguished himself academically or intellectually. Throughout his life, Hoover was addicted to hard work and believed deeply in science and technical expertise. Trump’s work habits have been erratic, and he famously does not trust experts. Hoover was devoted to his only wife, Lou, and never considered remarriage after her death two decades before his own. Trump was a playboy until well into late middle age, if not later.

Their pre-presidential careers couldn’t have been more different. Trump’s topsy-turvy business career in real estate and hotel development bled over into his real calling as a ubiquitous New York celebrity and then a reality-TV star of the highest order. He didn’t really need to accomplish anything more tangible than placing his “brand” on as many marquees as possible.

Hoover, by contrast, saved lives and fed the world, and was known as the “Great Humanitarian,” as David Frum recently observed:

Few if any Americans have dedicated more of their lives to the service of others than Hoover. A wealthy man by age 40, he turned his back on opportunities to earn more — and dissipated much of what he had gained — to devote himself to humanitarian work. As a private citizen, he organized food relief for German-occupied Belgium during the First World War. He undertook an even more ambitious task of rescue in Russia and Ukraine during the civil war that followed the Bolshevik seizure of power. Then, as Commerce secretary, he took charge of the response to the devastating flooding of the Mississippi Valley in 1927: floods that drove hundreds of thousands from their homes to temporary camps and left the region in economic shambles.

It wasn’t just that Hoover did these things well. He invented the idea that these things could be done at all, or at least done on any large scale.

When Hoover ascended to the presidency — not via some Trumpian upset but as a virtual entitlement — he was arguably engaged in the project of making America great for the first time. As biographer William Leuchtenberg recalled, Hoover knew that his biggest vulnerability was the level of expectation he had aroused:

I have no dread of the ordinary work of the presidency. What I do fear is the … exaggerated idea the people have conceived of me. They have a conviction that I am a sort of superman, that no problem is beyond my capacity … If some unprecedented calamity should come upon the nation … I would be sacrificed to the unreasoning disappointment of a people who expected too much.

The calamity struck just over six months into his presidency. Hoover did not handle it as poorly as posterity recalls, but he did make enough mistakes — mostly attributable to bad macroeconomic assumptions and a deep-seated antipathy to direct federal-government assistance to needy individuals — to very quickly make his reelection all but impossible.

Trump, by contrast, was a superman mostly in his own eyes, and from the very beginning divided the American people into ever-increasingly disparate judgments of his presidency, which barely seemed to correspond to any real developments in national life. He’s never been remotely as popular as Hoover was at the beginning of the Great Humanitarian’s presidency, and after three years of erratic conduct and chaotic governance, was at best an even bet for reelection when he ignored the early stages of the coronavirus threat. The question now is whether calamity will finally make him as unpopular as Hoover became under similar objective circumstances.

When Hoover was elected president, only two Democrats had occupied the White House since the Civil War. But you could already see the once-powerful GOP coalition beginning to unravel before the Crash demolished it: There had been a farm revolt in the middle of the 1920s; Catholic and Jewish immigrants (represented by Hoover’s first opponent, Al Smith) were consolidating power in urban areas; the “great experiment” of Prohibition had failed; high-tariff economic policies were threatening international trade. Arguably today’s GOP has been on the brink of disaster for a good while, with every demographic trend cutting against it, and Trump’s race-baiting and xenophobic right-wing populist message making expansion of the party base more difficult every day.

Will Trump’s base allow him to ride through calamity relatively unscathed, or will itself be blown to smithereens as the “greatest economy ever” falls into depression (a term Hoover pioneered as a less-alarming alternative to “panic”)? At least one academic, Helmuth Norpoth, argues that the economic downturn itself was not necessarily what did Hoover in:

The Great Depression, it appears, was treated by many as a natural disaster,” Norpoth writes. “Barely half of those voters who abandoned Hoover for FDR held the government at least somewhat responsible for the Depression.” In their view, “Wall Street was by far the biggest culprit. The government was a minor offender.”

An economic collapse caused largely by a global pandemic is in theory easier to treat as a “natural disaster” than was the Great Depression. But then again, expectations of government activism to counter such a catastrophe are much more widespread, and Trump has far less of a reservoir of goodwill than Hoover did when the stock market crashed.

The economy, moreover, was the one area of public life in which Trump earned relatively favorable assessments before it all went to hell. He and his advisers apparently think they can goose the economy into a steep recovery before he faces voters, at the considerable risk of enabling another, perhaps even deadlier, wave of coronavirus infections. The one thing reasonably clear is that if this gamble fails in any major particular, so will his presidency. Trump’s limited popularity is no more durable than Hoover’s, and he is a far less plausible unity figure than the most competent and compassionate man of his era, who is now remembered as feckless and cruel. Yes, like Herbert Hoover, Donald Trump has had the bad luck of encountering a national catastrophe that few saw coming. But Trump is unique in that many millions of Americans would view his political demise as a silver lining of that catastrophe, as the rainbow at the end of the flood. If he loses in November, it will be a defeat he has earned every day of his presidency. And his party may face a reckoning for years to come.