The Art of Navigating a Family Political Discussion, Peacefully

It works best when both sides really try.

Updated at 10 a.m. ET on March 26, 2019

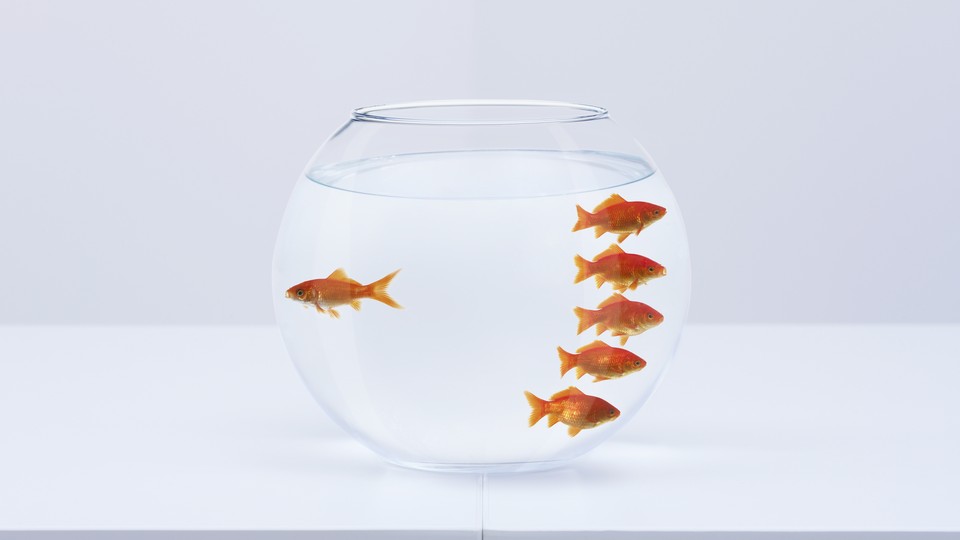

Lots of American families fight, but most are unlikely to fight about politics: In a study released last month on the extent to which Americans live in “bubbles,” 39 percent of respondents said they see political diversity within their families, as my colleague Emma Green reported. Meanwhile, “roughly three-quarters of Americans’ interactions with people from another political party happen at work,” and “less than half of respondents said they encounter political differences among their friends.” In other words, though the Thanksgiving Day family political argument is a beloved media trope, it’s not a reality for many families.

That said, some Americans do have political divides within their family—Kellyanne Conway and her husband, George, for example, have recently made headlines for having a spousal disagreement over politics on a very public stage. And for such families, the disagreements that result can be all the more painful, placing siblings or parents and children at odds with one another. In recent years, as political temperatures have risen, this has only become more common. In 2019, 35 percent of Republicans and 45 percent of Democrats said they would be unhappy if their child married someone of the opposing political party—a sharp increase from attitudes 50 years ago.

The depth of people’s political convictions, and the heightened distrust of those with different views, have both complicated and galvanized the work of Sarah Stewart Holland and Beth Silvers, the hosts of the podcast Pantsuit Politics and the co-authors of the new book I Think You’re Wrong (But I’m Listening).

“Sarah from the left and Beth from the right,” both former lawyers and now a writer and a business coach, respectively, became friends more than a decade ago as sorority sisters at Transylvania University in Kentucky—and today, they want to teach Americans how to have productive, civilized conversations about politics with their friends and family members.* Holland and Silvers started their podcast in 2015 as a way to have the kinds of conversations they wanted to see more of in America, in which each participant disaffiliates from her respective political party and they learn about and discuss particular political issues together. I Think You’re Wrong (But I’m Listening) aims to help readers engage in the same kinds of conversations in their own lives.

I Think You’re Wrong (But I’m Listening) provides a useful framework for readers on how to have these kinds of political conversations with those they love and yet disagree with—advising readers to, for example, “take off their jerseys” (that is, deliberately distance themselves from the full platform of policy positions supported by their chosen political party and instead examine each issue individually) and find their “whys” (talk about issues in terms of each person’s individual vision for what an ideal end result might be). It also advises readers early and often to abandon the idea of winning an argument or convincing other people of the wrongness of their positions, and to instead aim to have a conversation in which each party understands more fully why the other holds a given belief. Each participant, they emphasize, should approach the conversation with curiosity, a willingness to leave room for nuance, and grace, in the “goodwill” sense of the word.

In Holland and Silvers’ book as well as their podcast, the two exemplify the kind of productive conversation that can ensue when two people with what appear to be wildly different ideologies each show up with earnest curiosity, humility, and manners. In one chapter of the book, they describe researching the history of the American welfare system together, each learning that their respective understandings of how the system works, both in reality and in theory, were flawed in different ways. In an interview, however, they acknowledged that not every conversation about politics among people of different viewpoints has the same level of generosity on both sides—and conversations with unequal levels of generosity seem to happen more often nowadays, in a time when Americans of opposing political views trust one another less than in the past.

“What we always say is, it’s not necessary for someone to give grace to receive it. It’s not necessary for the other person to be totally openhearted and patient and willing, especially with family members, for [you] to be openhearted and patient and willing to give all the curiosity and grace in the world,” Holland said. The hope, she said, is that the family member will “be disarmed and hopefully more curious for the next conversation—more willing to listen in the next conversation, because someone showed up and said, ‘I’m not coming here to try to convince you or to oppose you, but merely to try to understand better where you’re coming from.’”

Sometimes when people hear about the book that Silvers and Holland have written, they expect a guide on how to get their sibling or parent or child who votes differently to listen to them, Silvers added. She noted that it’s common to see people “smash the trust” in their otherwise loving family relationships because of political beliefs, “often without knowing very much about why they’re on opposite sides of an issue.” So when relatives talk politics, she said, the conversation has to be a trust-building process.

When I asked Silvers and Holland whether they’d been forced to recalibrate or reconfigure their philosophy in the wake of the election of Donald Trump, both women acknowledged that advising other people on how to navigate their conversations with family members about politics has only gotten harder since 2016. “We often say that we set out to do ‘nuanced’ and then the universe gave us Donald Trump,” Silvers quipped.

One reason Holland and Silvers advocate for having these tough conversations in the first place is because they can help enlighten what people of seemingly opposing positions have in common; for example, though Holland supports a nationalized single-payer health-care system and Silvers has doubts about the real effectiveness of such a system, they found through conversation that they both “wanted high-quality health care at affordable prices for all Americans” and worked outward from there in discussing how to achieve it. But in the past two years, as they acknowledge, many have lost faith in the notion that deep down most of us want to see all Americans have opportunities to thrive, but we just have different ideas of how those opportunities could be created. That good-faith reading of political differences—as merely different theories for how best to achieve the same created-equal, endowed-with-certain-unalienable-rights goal—disintegrated, for many, right around the time that self-described white nationalists rejoiced at the election of a U.S. president they believed represented their core values, leaving many with new fears about the motives of their friends, spouses, and family members who voted differently from them.

Silvers and Holland have found some new boundaries for their own dialogue as a result. “For us, there are bottom lines in protecting the dignity of people around their race, sexuality, gender identity, and religion that are inviolable,” they write in I Think You’re Wrong (But I’m Listening). Some of their listeners, they add, were surprised when the pair declined to take a “both sides” approach after violent incidents occurred at a white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017; many listeners, they found, had expected them to defend the white supremacists’ right to free speech. (“Plenty of people are willing to use their platforms to emphasize freedom of speech and assembly,” Silvers later wrote in a blog post addressing listeners. “In this moment, in this instance, I’m not willing to use mine that way. My voice, my work is to say, ‘That’s wrong. That’s unacceptable in America in 2017, and our businesses and politicians and families must say so in both words and actions.’”) Silvers mentioned in conversation that she and Holland also don’t take a “both sides” approach to marriage equality: “Marriage equality is a bright line for us. We have not invited anyone into our conversations who advocates against marriage equality.”

Ultimately, however, Silvers emphasizes that while they perhaps won’t share a podcast or any sort of public platform with people whose beliefs might infringe on their commitment to human rights, they still have to peacefully share a country with them—and sometimes their readers and listeners will have to peacefully share homes, dinner tables, holidays, and beds with them, too. So in cases where people find themselves trying to engage in a political conversation with a parent or a sibling or another relative who espouses beliefs that dehumanize others or advocates for the denial of human rights, Holland said, the best course of action is to avoid engaging in the same type of dehumanizing behavior. “The stakes are high and it feels so easy and so justifying to be angry—to lash out, to dehumanize the other side,” Holland said. “But the best reaction to a leader or an administration that does that is like a conversational version of nonviolent resistance.”

The emergence of Trump as the polarizing figure around which families divide themselves has also led Holland and Silvers to advise their readers and listeners to “zoom out” and move their political discussions as far away as possible from the administration itself. Better than talking about Trump or the border wall, Silvers offered as an example, is talking about immigration in general; better still, she said, is starting with open-ended questions about what the people she speaks with believe about immigration. When Silvers, a Republican who does not support Trump, talks with her friends and family members who do, “I’ll say things like, ‘Who should get to come to America? And where should we get to go—if I wanted to move to Canada, what should that process look like?’” she said. “Let’s have a broader discussion so we’re not talking about an individual.”

Holland, who worked for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign and whose father is a Trump supporter, learns a lot about how to engage in political conversations in the current political climate through the ones she has with her dad. She’s learned through her conversations with him, for instance, that lecturing someone with facts and figures isn’t nearly as conducive to an enlightening, polite exchange as sharing personal or firsthand experiences with policies or issues. “You can’t open with, ‘Let me share this data.’ You have to start with, ‘Here’s my story, as I see it,’” she said. “When people see you supporting [a policy because of] something you know to be true, as opposed to you trying to convince them it’s true, it changes the tenor of their responses to it.” And in a time when published materials of all kinds are routinely doubted or accused of political bias, a personal story is more difficult to dismiss out of hand as “fake news.”

Of course, Holland and her dad sometimes find that they just “see the world very differently,” she said. “There are often conversations in which he’s describing a world or a country that I just don’t see anywhere in my experience,” and sometimes, she admitted, “he can’t see the truth in what I’m saying, and we’re totally at odds with each other.”

And that’s when Holland has to draw on one of the lessons she and Silvers promote in the book: Remember that agreeing on matters of politics should always be lower on the priority list than maintaining a healthy, caring relationship. “There’s a moment sometimes [where we have to remember], Okay, we’re father and daughter. We love each other. We’re just going to move on for now,” Holland said. “It’s a long game.”

*This article originally misstated the profession of one of the authors.