Why Wisconsin's Covid Breakthrough Numbers Show the Power of Vaccination

When the state health department compiles figures about people vaccinated for COVID-19 who become infected with the virus, the role of age is paramount in understanding differing impacts across the state's entire population.

By Will Cushman

October 12, 2021

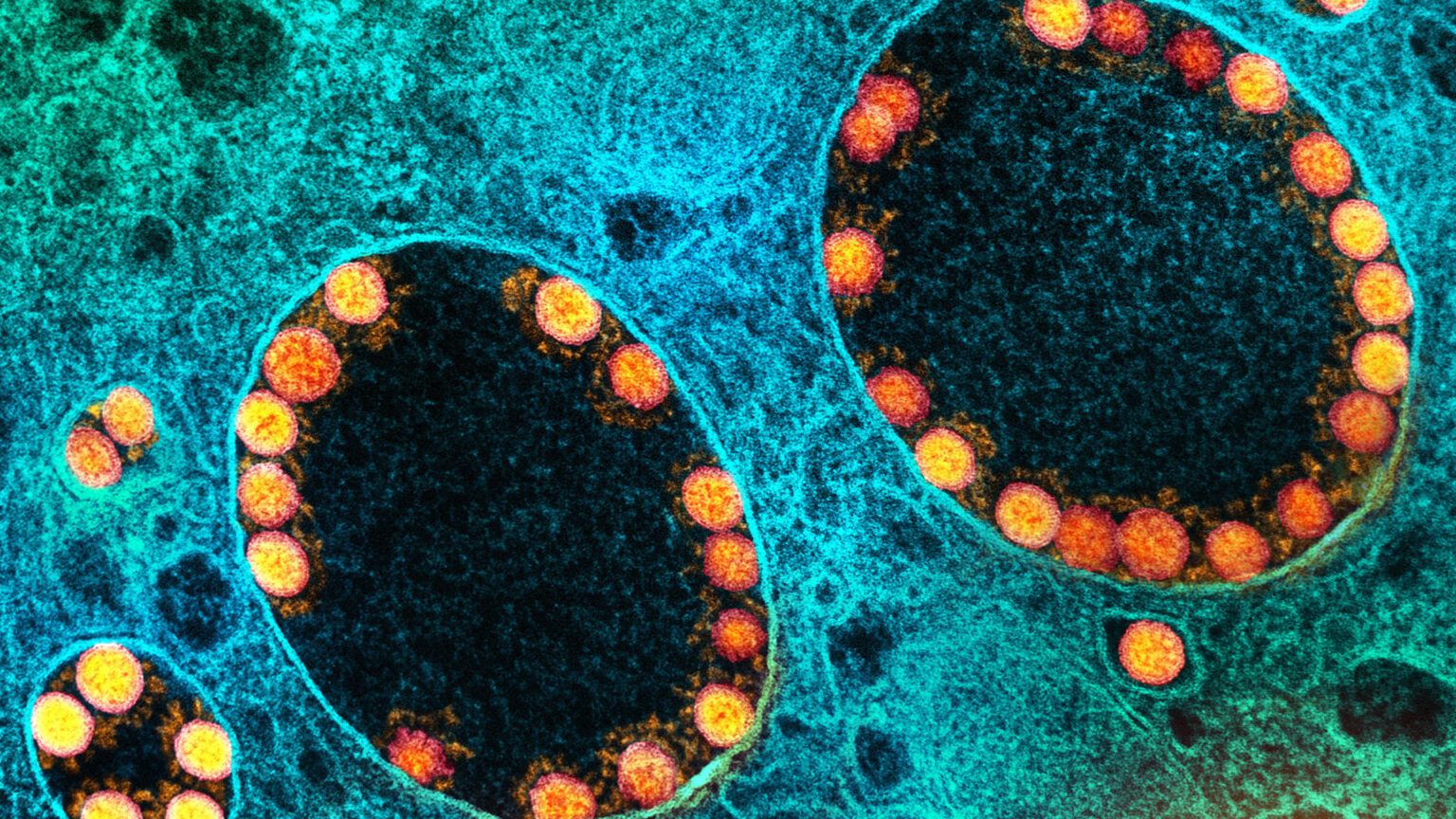

A transmission electron micrograph shows SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, in yellow-orange hue, within endosomes of a heavily infected nasal olfactory epithelial cell. (Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

Even as the Delta variant of COVID-19 fuels a rise in new cases among Wisconsinites who are fully vaccinated for the virus — called breakthrough infections — public health officials affirm how these numbers nevertheless illustrate the protective power of vaccines.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services points to data showing a gap in the rate at which fully vaccinated and not fully vaccinated people come down with COVID-19, along with much wider gulfs in rates of covid-related hospitalizations and deaths between groups.

In its September 2021 breakdown of breakthrough statistics, the agency reported the covid-related hospitalization rate among people who were not fully vaccinated was 8.5 times higher in August than among fully vaccinated people. The gap in the death rate between the two groups was even wider — about 10.6 times higher for people who weren’t fully vaccinated.

But these statistics are not a result of simple comparisons between vaccinated and unvaccinated Wisconsinites. They reflect instead the rates of hospitalizations and deaths among the two groups after adjusting for age.

Adjusting disease rates for age is a common practice in epidemiology. The practice is crucial for understanding the impacts that a disease like COVID-19 has on a large and varied population.

“We adjust for factors like age because we identify factors like age as being confounders,” said Ajay Sethi, an epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In epidemiology, a “confounder” is essentially any personal characteristic that could make a difference in someone’s risk for developing a disease or how they will fare after being diagnosed with a disease. A personal characteristic like age is a confounder when it also has a relationship to risk factors, decisions or habits being studied in relation to a disease.

In the context of COVID-19 breakthrough numbers, age is a confounder because it’s related to both risk for serious disease and vaccination rate. Among all confounders, age is a big one — perhaps the big one.

“Age is considered in epidemiology as a universal confounder because everything tracks with age,” Sethi said.

Disease rates and outcomes almost always diverge by age, he explained. Chronic disease rates are higher among older people, rates of sexually transmitted infections tend to be highest among young adults, seasonal influenza symptoms are usually most severe in the very young and very old, and so forth.

A year and a half into the pandemic, it’s understood by medical professionals that certain people are more at risk of developing severe symptoms and dying from COVID-19, including those who are immunocompromised and particularly the elderly.

This lopsided risk gap by age is vast.

According to the state health department, the percentage of people in Wisconsin under 60 who have died from COVID-19 after a diagnosis is lower than 1%. Moving up the age scale, about 1% of Wisconsinites in their 60s who have tested positive for covid have died from it, compared to 5% of those in their 70s, 13% of those in their 80s and 24% of people 90 and older.

Hospitalization rates similarly climb with age.

Age disparities in COVID-19 severity are obvious even among fully vaccinated people who nevertheless get a breakthrough infection.

Wisconsin data show that between February and August 2021, about 47 out of every 100,000 fully vaccinated Wisconsinites 65 or older were hospitalized following a breakthrough infection. That compares to about one per 100,000 among 18 to 24-year-olds, three per 100,000 for 25 to 34 year-olds and incrementally higher rates in older age groups.

At the same time, data show that breakthrough deaths are close to non-existent in Wisconsinites younger than 55. However, these deaths do rise to a little less than six per 100,000 people 65 and older.

These differences reflect a national trend that has informed the view among regulators at the Food and Drug Administration that, all else being equal, older Americans stand to benefit the most from immunity-bolstering booster shots. (Even though some people have been advised to get boosters, a rise in breakthrough infections, such as in Israel, does not on its own necessarily indicate waning vaccine effectiveness; simple math dictates that as more people become vaccinated, more breakthrough cases will occur.)

Even as the epidemiology of breakthrough cases becomes clearer, these figures also importantly emphasize how the risk COVID-19 poses is significantly larger for unvaccinated Wisconsinites within all age groups.

Between February and August, covid hospitalization rates were between six and 15 times higher among unvaccinated Wisconsinites in all age groups eligible for vaccination. For adults 55 and older, death rates were between eight and 27 times higher among those who were unvaccinated, depending on the age group. (Death rates were zero for fully vaccinated adults 54 and younger and both vaccinated and unvaccinated children under the age of 18).

Not only do disease outcomes vary considerably by age, but those Wisconsinites who are fully vaccinated are quite different from the group who are unvaccinated when it comes to age. There are no children younger than 12 among the fully vaccinated group, and significantly fewer adolescents and younger adults in general. Meanwhile, a large majority of elderly Wisconsinites are fully vaccinated.

The just over half of Wisconsinites who are fully vaccinated are therefore, on average, much older than the just under half who are unvaccinated or partially vaccinated.

Adjusting for age allows epidemiologists to directly compare these two very different groups.

“It gives you a chance to compare apples with apples,” Sethi said.

To do so, epidemiologists first must know the number of people who are fully vaccinated or not, along with their ages. This information can be gleaned from online databases where hospitals, health departments and vaccinators upload records of the vaccines and reportable diseases, including covid, each Wisconsinite gets. Vaccine records are maintained in the Wisconsin Immunization Registry, while confirmed covid cases are reported through the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System. Records in both databases include information like county of residence, age and race.

With these records in hand, the state health department knows the age breakdown of the fully vaccinated group and the prevalence of breakthrough cases, hospitalizations and deaths by age. Epidemiologists then determine breakthrough rates in fully vaccinated Wisconsinites by age and adjust those rates to reflect a “standard population.”

In the case of Wisconsin’s breakthrough data, the standard population is a 2019 U.S. Census Bureau estimate, according to Elizabeth Goodsitt, a spokesperson for the state health department. The estimate includes a population breakdown by age group.

By adjusting breakthrough statistics in this way, the state health department is essentially asking this question: What would the COVID-19 infection rate, hospitalization rate and death rate look like if those calculated for fully vaccinated Wisconsinites in each age group were extended to the entire population estimated to be in each age group in 2019?

Epidemiologists then do the same for Wisconsinites who are not fully vaccinated.

In this way, Sethi said, the adjusted rates for each group are “fictitious” and not meaningful on their own.

“Mathematically you can come up with very different adjusted rates, depending on what standard population you use to do the adjustment,” he said.

But so long as the same standard population is used for both groups, comparisons between the adjusted rates are anything but fictitious — these figures are a core scientific principle of epidemiology.

That’s precisely what health officials are aiming for as they track breakthrough rates to better understand how well COVID-19 vaccines protect against infection, hospitalization and death.

As of August, the age-adjusted data in Wisconsin continued to show a stark divide in disease outcomes by vaccination status. The state health department is set to release statistics for September on Oct. 15.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated with additional explanation about the role of confounders in epidemiology.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us