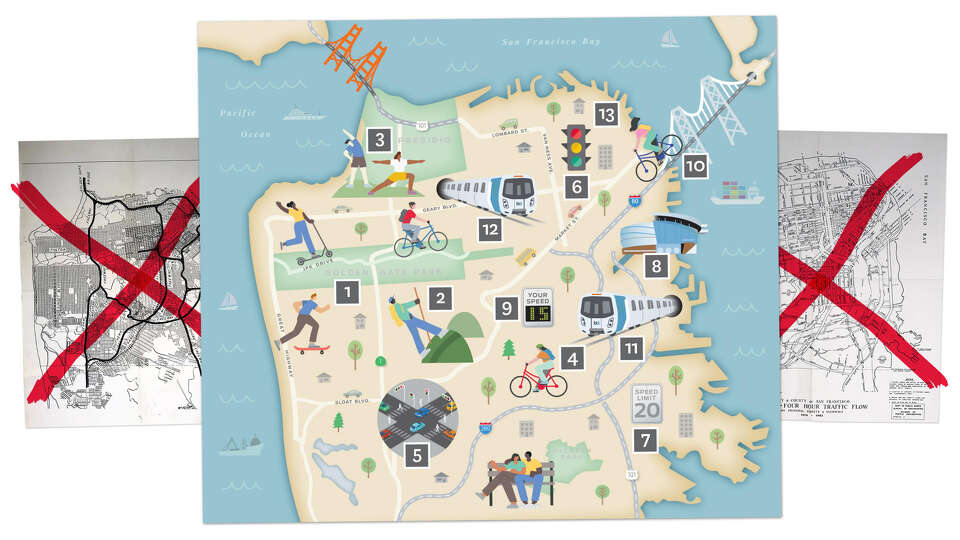

“Give me a tunnel-boring machine, and I’ll solve a lot of problems in this city.” The first time I saw Twitter personality Burrito Justice type this on the social media platform, way back in 2012, I thought it was science fiction. The pro-bicycle, pro-transit advocate, real name John Oram, once mapped out a system of gondolas connecting the hills of San Francisco. It was an entertaining distraction to stoke our imaginations, while real life featured glacial changes toward a pedestrian-friendly, bike-friendly city.

Leap forward to 2020, and we’re in the middle of a pandemic that looks to be the largest single city-reshaping event since the 1906 earthquake and fires; San Francisco is becoming bikeable and walkable by necessity, adapting and improvising at incredible speeds — with bureaucracy no longer an insurmountable roadblock to change.

Read more

JFK Drive and The Great Highway

Failing to enshrine this change means Biketopia S.F. is over before it started

Easy

Considerable

Jay Beaman was a wine director and manager at Firefly before the pandemic, and he hopes to return to that life in the years to come.

Right now, he’s using his unemployment to build a pro-bike army, establishing Scenic Routes Community Bicycle Center, filling his Western Addition living room with parts and tools, and fixing bikes for free. He’s put 25 friends and strangers back on the road, some on bikes that hadn’t been ridden in more than a decade.

“It just kind of felt cool to think, ‘OK, this is what I do now. I fix bikes,’” he said.

The first test of the army’s strength will be enshrining car-free JFK Drive and the use of the Great Highway for pedestrians and bikers. The debate to keep JFK Drive car-free permanently has been going on for a half century, with a motley crew of advocates fighting against well-moneyed museum boosters and other old-guard San Franciscans. The Great Highway seemingly came out of nowhere. Both changes have proven that their utility trumps any inconvenience.

If the car-embracing forces win on these two points, then we’re clearly not in a revolution. Biketopia S.F. is over before it started.

Twin Peaks

Going car-free would make it akin to a local Mount Everest for bikers, walkers and runners

Easy/Challenging

Limited

When columnist Heather Knight and I rebooted the outdated 49 Mile Scenic Drive as a more walk-friendly, bike-friendly route, we both wanted to remove Twin Peaks from the map. In a social media mutiny, Chronicle readers overruled us, claiming the landmark’s vistas. We saw an overrated tourist spot, and a haven for smash-and-grab robbers. They saw the centerpiece vista point in San Francisco, with views that overcome its poor pedestrian and bike access.

Now it’s the best of all worlds, closed to cars and a sort of Mount Everest for bikers, walkers and runners seeking the best combination of exercise and beauty in the city.

Twin Peaks will test the creativity of city leaders, who must ensure that when the pandemic is over, everyone has access to the view. Whether it’s a system of shuttles, disabled parking at Christmas Tree Point or something more inventive (a tourist-friendly weekend Muni line like the 76x Marin Headlands?), the future of Twin Peaks should take personal vehicles out of the pole position.

Presidio Golf Course

Strike one for the proletariat and turn the course into a park for the people

Easy/Challenging

Limited

For a few lovely weeks this spring, the Presidio Trust opened up the publicly owned 150-acre Presidio Golf Course to the proletariat, and a green space used by a small fraction of the population was enjoyed by the masses, who exercised safely and fell in love with the Presidio all over again.

The Presidio Trust is weathering tough times, and the revenue they receive annually from the golf course (about $9 million) is one of the few stable parts of their budget. So let’s start small, dedicating one Sunday a month for the people, with hopes of expanding Presidio People’s Park to every Sunday when times are better. And consider the six other city-owned golf courses (one is in Pacifica) when thinking about expanding access to public spaces.

Slow Streets city-wide

Expand and make permanent the program's traffic changes

Challenging

Considerable

Cyril Magnin and Marvin Lewis, two 20th century city leaders who helped shape San Francisco, used to take a daily morning walk together from their Sea Cliff homes to their Financial District offices.

Salesforce co-founder Marc Benioff (Lewis’ grandson) tells this story, espousing the need for business leaders, especially the wealthiest ones, being in touch with their stakeholders. Lewis is the father of BART. Magnin’s philanthropy changed the city’s art scene. How many of their best ideas came walking and talking as they crossed the city, running into fellow citizens, and allowing themselves to fall in love with San Francisco a little more every day?

During the coronavirus, the SFMTA-supported Slow Streets program has limited car access on 30-plus miles of residential roads, creating a safe network for exercise and families to play. SFMTA director Jeffrey Tumlin recently reported that the Slow Streets are receiving 95% support. (“The complaints are about, ‘Why haven’t you done this in my neighborhood yet?’ ”)

Paris, Milan and Seattle have all committed to making many of their pandemic traffic changes permanent. San Francisco leaders should keep experimenting, making some forever Slow Streets and building a network, until San Francisco becomes a city where a pedestrian can safely walk down the middle of the street from one end to the other.

Daylighting, raised crosswalks and no right turns on red

Vanilla? Maybe. But these safety measures could make areas like the Tenderloin safer

Very Challenging

Considerable

Imagine a tragedy that happened every year at the Fillmore Auditorium. Every fan was injured, every band member died and every employee at the Fillmore that night was critically injured.

If it was preventable, wouldn’t the city move mountains to stop this annual crisis?

That’s the situation in San Francisco, where, four years after Vision Zero SF was adopted to eliminate traffic fatalities, more than 3,000 people were injured and 29 died in motor vehicle incidents last year.

The safety measures listed here are not very sexy, but could collectively make a huge difference. Daylighting, already approved by the city but not completed, opens up parking spaces near intersections, so drivers and pedestrians have better visibility. Banning right turns on red lights and raising crosswalks with visible painting will also make intersections safer.

Walk SF executive director Jodie Medeiros points out that the Tenderloin, home to some of the most dangerous streets in San Francisco and the city’s most vulnerable populations, continues to prioritize fast lanes for commuters traveling from the western neighborhoods to the Financial District.

“Long term, we can’t forget that every single street on the Tenderloin is part of the high-injury network,” Medeiros said. “We cannot forget that 30 people die a year in traffic violence.”

13 mph timed traffic lights

Timing traffic lights to bike-friendly speeds helps cars and bikes to co-exist

Challenging

Considerable

I remember the first time I biked down the Folsom “Green Wave.” It was the moment I turned from being “someone who bikes” to viewing biking as a permanent lifestyle.

Having traffic lights timed to a bike-friendly 11, 12 or 13 mph on main thoroughfares through residential districts helps to give cars and bikes a more peaceful relationship; less like predator and prey, and more like a dolphin and whale, using the same current to get where they need to go.

Portland has timed traffic lights, slowing cars to speeds that limit fatalities, and it’s less stressful for everyone. Instead of fits and starts, you get to your destination at a steady cruise.

Tenderloin streets, including Eddy and Ellis, should be added to the Green Wave as a matter of life and death. The use of 13 mph limits should be prioritized wherever bikes and cars share the road.

20 mph city speed limit

Dropping the speed limit to 20 miles per hour would increase the survival rate for those struck by cars to 90%

Very Challenging

Significant

Don’t blame San Francisco city leaders for their inability to change their own speed limits. They’ve been trying.

Speed limits are set by the State of California, using outdated rules created to stop small-town “Dukes of Hazzard”-type police forces from setting up speed traps. Speed limits are based on average speeds in the area, which mandates that if 85 percent of people drive at one speed, that should be the speed limit. (And if it’s close, round up.)

Studies show the survival rate for human hit by a car at 40 miles per hour is about 35%. Drop the speed limit to 20 miles per hour and that rate rises to 90%.

The last attempt in 2018 to give locals more authority over speed limits died before it started, with opposition from the CHP, Teamsters and trucking industry reps. The pandemic has proven that most voters are eager to prioritize lives over money. And a 20 or even 25 mile per hour city-wide speed limit could save many lives.

Bayview to Chase Center

The harrowing trip by bike should be made safe for everyone aged 8 to 80

Very challenging

Significant

When Chase Center opened on Sept. 6, 2019, to the power chords of Metallica and the San Francisco Symphony, the new arena became one of the most bike-friendly sports cathedrals in history, with Terry Francois Boulevard including a two-way bike lane that loops to the front of the arena like a green welcome mat, and valet parking for 300 bicycles.

The rest of the city is way behind. A trip from the nearby Bayview to the Golden State Warriors’ home is a harrowing experience, all but forcing bicyclists to risk their lives on Third Street. Neighborhoods including the Ingleside have no clear bike-first channel. The so-called hairball, where the bike lane on Cesar Chavez Street ends at a web of freeway off-ramps and broken street lights, is derided by all who endure it.

“I think Jeffrey Tumlin and Mayor (London) Breed should have to ride from the Mission to Bayview on a bike every single day until they fix that hairball,” bike advocate Jay Beaman said. “It’s so unbelievably unsafe.”

In our transit utopia, everyone in San Francisco ages 8 to 80 should feel safe making that trip to Chase Center on foot or by bike, whether it’s a fan living in housing near Hunters Point, a retiree working as an usher who lives in the Sunset or Warriors coach Steve Kerr coming from his house in Presidio Heights.

Automatic speed enforcement

Automating traffic ticketing would make streets safer — and remove racial bias

Very challenging

City-changing

Automatic speed enforcement is another bureaucratic mess, requiring a change in state law that would allow California cities to set up automatic traffic ticketing near the city’s most dangerous intersections. (It was last defeated in 2018.)

But this one seems to align with the times. Not just the pandemic, but the Black Lives Matter protest movement and our daily dose of disturbing statistics on people of color being targeted during traffic stops.

Automated speed enforcement, and the red light cameras already in place, remove police and implicit racial bias. Activists and transit planners seem to believe that this move, more than any other, could end up saving lives in the Tenderloin, Chinatown and other places where the city’s most vulnerable citizens live.

“What we’re talking about is a public health crisis, and I think people forget about that,” WalkSF’s Jodie Medeiros said. “(These) are not victimless crimes. It’s mostly children, it’s mostly seniors in low-income neighborhoods.”

Bay Bridge

Imagine crossing the Bay on a dedicated bike platform or converted traffic lane

Very challenging

Considerable

A Bay Bridge bike and pedestrian lane to connect S.F. and Oakland isn’t going to happen without public support. Like Beaman, Wiedenmeier believes that army is being built right now.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t get two or three text messages or emails or messages about where to find a bike, if we have resources available,” Wiedenmeier said. Online classes are growing, and the group’s Bike It Forward program gets refurbished bikes in the hands of first-timers.

“And that,” Wiedenmeier says, “is what’s going to build momentum for some of these bigger projects.”

It will take support, up to the governor, for a project the size of a Bay Bridge bike lane, which would require adding a bike platform adjacent to the bridge or repurposing one of the five lanes. And there’s definitely no money for it today. But the city is filled with lasting infrastructure that looked impossible during the Great Depression, immediately followed by some of the most ambitious change in the city’s history.

Second BART tube

A new transbay rail crossing would double our rail capacity

Very challenging

City-changing

Our recent past is filled with construction boondoggles: the late, expensive and leaky eastern span of the Bay Bridge, the broken-on-arrival new Transbay Terminal and the three-years-late Central Subway.

Faith is required to dream of a second BART tube that isn’t mired in similar disappointment, but there’s precedent. The pre-1906 earthquake San Francisco city government was one of the most corrupt in history, building an earlier City Hall so kickback-ridden and faulty that the quake revealed literal garbage had been used to fill the walls. A group of business leaders banded together and helped steer a reinvented San Francisco that was better than before.

Add to the fact that this was considered a foregone conclusion even before the pandemic, and a new transbay rail crossing doesn’t seem like such a long shot, doubling our rail capacity across the bay and easing pressure on existing Market Street stations, while giving new neighborhoods access to transit. Who doesn’t want that?

Geary Boulevard

A Geary subway would fix one of the city’s biggest people-moving problems

Very challenging/science fiction

City-changing

The Central Subway, a stubby 1.7-mile Muni Metro track from Chinatown to Fourth and King streets, will be more than three years behind schedule if it isn’t delayed (yet again) before its end-of-2021 planned opening. But that doesn’t mean we should stop. It just means we should be more efficient, with better oversight and a priority of utility over grandeur.

John Oram points to the Barcelona model, where subway stops are quickly being added at a fraction of the cost of San Francisco’s network. Turn that tunnel boring machine on and never turn it off again.

“Tunnels are pretty cheap; it’s the stations that cost so much money,” he says. “You just put an escalator in; you drop a big station in a tube. ... It doesn’t need to be this massive box, which gets really expensive.”

Fisherman’s Wharf seems like the next logical spot for the Central Subway, then extending out to the Marina District and Presidio. But the we-can-die-happy-now moment will be a subway along Geary Boulevard, most realistically as a line extending off the second BART tube. Promised for more than 100 years, a Geary subway would fix one of the city’s biggest people-moving problems, forever being triaged by the overworked 38 Geary bus line.

“It’s a challenge to get to the Marina. The Presidio … oh my God,” Burrito Justice said. “Imagine being able to take the subway to most of your kids’ games. That’s just not feasible now.”

Downtown

By limiting vehicles, we could follow Oslo's model toward a car-free utopia in the city's center

Science fiction

Revolutionary

As other items on this checklist show promise, we’ll be ready for the big dream: limiting vehicles from a large portion of downtown and rebooting it for bicyclists, walkers and transit.

Oslo is doing this right now, making only small compromises for the goal of a car-free utopia. Years from now, with enough momentum, turning busy downtown streets into multi-use bike pathways, benches and patio seating may seem no more crazy than tearing down the double-decker freeway next to the Ferry Building.

There was a time that the Golden Gate Bridge looked like science fiction too. The ferry companies took out ads in The Chronicle, claiming spanning a bridge between San Francisco and the Marin Headlands would harm tourism, or that it would be bombed and trap our Navy fleet.

We’re starting small, at the street level, right now. If we open our minds to the potential of the city, anything seems possible.

“I think sometimes we take for granted that a street is a street and it will always be that way,” Wiedenmeier said. “Ask yourself if it’s dangerous for a senior citizen to cross the street, if it’s not safe for a family to bike with their children to school. And that’s when we have to ask the question: ‘Is this really serving the community?”