Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

What should Australia do about…

its politics being too white?

By Osmond Chiu

Australian politics is too white. It is less diverse than comparable countries such as the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada. This is embarrassing. We cannot be “the most successful multicultural society in the world”, as former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull wrote, if our institutions do not reflect Australia’s cultural diversity.

The lack of diversity hurts our democracy. It leads to more disconnected, myopic and polarised debates about race and national identity. The homogenous nature of Australian politics is one reason why politicians find it difficult to deal with issues like foreign interference because there is insufficient cultural and political knowledge of the foreign entities the government seeks to legislate against. A truly representative parliament is necessary if we want Australia to successfully navigate big foreign and domestic policy challenges, and to reflect the values of equality which Australia stands for.

Chinese-Australians, in particular, have found it challenging to participate in politics over the last three years because of a growing public perception that the Communist Party of China (CPC) operates within and influences the actions of Chinese-Australian communities. This includes the use of political donations.

In order to create a more representative parliament, Australia needs to do three things:

1) Political parties should publicly report on their cultural diversity and adopt targets for winnable seats;

2) Political parties and Chinese-Australian communities must train and foster a group of skilled and experienced candidates;

3) The Commonwealth must rebuild trust in political institutions by establishing a national integrity commission and capping political donations.

These measures will enable the setting of goals for improving representation, maximise chances for culturally diverse candidates to be elected, and help address concerns about undue influence in politics.

How severe is political underrepresentation in Australia?

The full extent of underrepresentation is unknown because measurable data on the cultural diversity of Australian political parties does not exist. Without data, it is difficult to measure or even set goals to improve Asian-Australian (and Chinese-Australian) representation.

The major political parties do not collect and publish nationally consistent data on their cultural diversity. Parties require reports on other forms of representation such as gender. The ALP National Constitution, for example, requires an annual affirmative action report to the National Executive that reports on gender for party positions, union delegations and public office preselections.

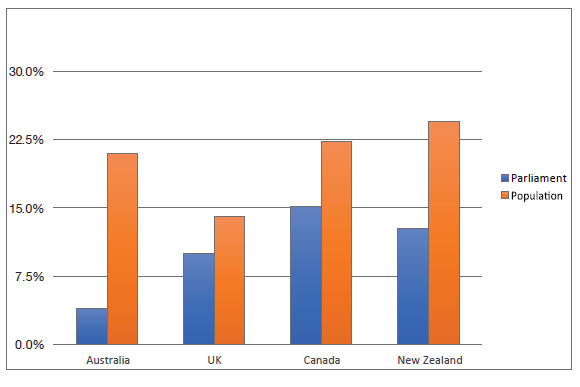

Australia’s federal parliament is less representative than comparable English-speaking Westminster democracies. One in 10 MPs elected in the recent British election are from black and minority ethnic backgrounds.1 At the 2019 Canadian federal election, 15.1 per cent of MPs elected were visible minorities.2 In New Zealand, 6.7 per cent of MPs are of Pacific Peoples ethnicity and 6.0 per cent are Asian.3 In contrast, only nine of 227 or 4 per cent of Australian federal MPs have non-European heritage.4

Representation of non-European heritage national MP vs diversity of national population

Source: Data from Australian Human Rights Commission, Leading for

Change: A blueprint for cultural diversity and inclusive leadership revisited;

British Future; Kiwiblog; Policy Options; 2016 Canadian Census; 2011 United

Kingdom Census; 2018 New Zealand Census

Underrepresentation extends to senior leadership levels. Not a single Australian federal minister is from an Asian-Australian background. In stark contrast, upon becoming Prime Minister, Boris Johnson said he would form a “cabinet for modern Britain”, including four British Asians in senior positions. In Canada, six of the 37 members of the Cabinet are Canadians of Asian heritage. Australia lags behind its peers in every aspect of political representation of culturally diverse minorities.

Why is representation so low?

The barriers for all Asian-Australians are:

1) Political parties have a small pool of candidates because they do not attract nor promote culturally diverse members; and

2) Political parties do not see preselecting Asian- Australians as electorally advantageous; Chinese-Australians face additional hurdles due to the foreign interference debate.

While parties have courted Asian-Australian communities, they have done little to attract individual party members. Parties have established associated groups, for example, Liberal Party Chinese Council or Sub-Continental Friends of Labor, but these are primarily vehicles for fundraising with no role in party decision-making. These groups provide only a limited role for individual party members to step up.

Chinese-Australians have been the main focus of discussions about Asian-Australian representation in politics. Asian-Australians are 14.7 per cent of the population. Chinese-Australians form the largest subgroup (5.6 per cent).5 Engagement is often transactional and focuses on fundraising or numbers for support in preselections rather than improving representation. Former Victorian Labor candidate Wesa Chau noted that when she first joined, she was labelled a “stack”, someone signed up to vote for specific candidates in party elections. Chinese-Australian members of the ALP have criticised this transactional culture as it undermines public trust in democratic processes. Similarly, former NSW Liberal candidate Scott Yung has stated that political engagement with Chinese-Australians cannot solely be about donations.6

Improving representation will require addressing negative perceptions about politics and navigating generational differences within communities. Attempts to encourage interest in party politics have failed; for example, the Chinese-Australian Forum, a non-partisan body, trialled “Opportunity Meetings” to promote participation – without success. Political engagement continues to be dominated by older generations with existing relationships and who tend to be more comfortable with transactional politics. A generation of younger Chinese-Australian leaders is missing, a gap the communities urgently must address.

The professionalisation of politics compounds the problem of a lack of diversity in Australian politics. Candidates tend to be insiders with existing party networks. Almost 40 per cent of federal MPs in 2018 worked as advisers in state or federal government before running for office, up from less than four per cent in 1988.7 Former Liberal Minister Craig Laundy has commented on the need for more culturally diverse representatives, noting many MPs had been through a “factory process” which involved working as a staffer.8 Moreover, culturally diverse candidates who do get preselected tend to be chosen for unwinnable seats.9

Chinese-Australians face particular challenges when trying to enter politics because of a growing perception that those with strong Chinese community connections could have links with individuals and organisations associated with the Communist Party of China. In NSW, currently only three state MPs and not a single federal MP has Chinese heritage despite constituting nearly 10 per cent of the population in Sydney.10 In Victoria, there is only one state and one federal MP of Chinese background. Chinese-Australians are an electoral liability. Research has found a candidate of Chinese background decreases the probability of voter selection by 6.4 per cent.11

The foreign interference debate has made improving the political representation of Chinese-Australians even harder. The investigation by the Independent Commission Against Corruption into political donations to NSW Labor and ongoing questions about Gladys Liu’s membership of groups linked to the CPC have also created negative perceptions about Chinese-Australians in politics. It is made worse by unverified claims, such as those by Clive Hamilton that preselected candidates of Chinese ethnicity are “likely to be trusted by Beijing”.12 As former Labor candidate Jason Yat-sen Li has stated, “this environment is tremendously disenfranchising for Chinese-Australians.”13

One Chinese-Australian politician in Sydney told a China Matters researcher that it is much harder to be a politician of Chinese heritage now compared to three years ago. The current political climate will accentuate underrepresentation unless action is taken.

Addressing undue influence in politics

The establishment of a national integrity commission and stipulation of a cap for political donations may help address some public concerns about undue influence in politics that has become associated with Chinese-Australians. The 2019 Australian Election Study found only 25 per cent of Australians believe people in government can be trusted, the lowest it has been since the survey began in 1979.

A national integrity commission would be a best-practice independent, broad-based public sector anti-corruption commission for the Commonwealth. The body would investigate at the federal level suspected corruption and misconduct of MPs, political staffers, ministers, public servants and members of the judiciary. It would also be responsible for promoting integrity and preventing corruption. State-based anti-corruption bodies would be obliged to abandon their investigations once it crossed state borders. Currently, there are no federal mechanisms to hold public hearings and publicly hold federal office bearers accountable.

Both a national integrity commission and a cap on political donations are mechanisms to address distrust in government because it will help counter the belief that political decisions are influenced by money. It would also affect the underrepresentation of Chinese-Australians in politics by addressing public fears about undue political influence, which is tied to concerns about donors with alleged links to the CPC. Rebuilding the public’s trust in our democratic processes will help combat negative perceptions, which the foreign interference debate has given rise to and made harder for Chinese-Australians to be involved in politics.

Policy recommendations

- Political parties should draw on best practice experiences of other countries with diverse populations to measure and publicly publish data on the cultural diversity of its parliamentarians, candidates, office bearers, delegates to key party forums, staffers and party office staff.

- Political parties should foster a group of culturally diverse candidates by diversifying party membership, establishing specific training and mentoring programs and compiling recommended candidate lists.

- Political parties should adopt a target of 20 per cent of culturally diverse candidates for winnable seats. Preselection processes should be halted if no genuine attempt is made to find diverse candidates.

- Parties should provide more paid staffing and campaign opportunities to culturally diverse members to ensure party offices and staffers reflect the community.

- Chinese-Australian communities should establish a campaigning fellowship for young Chinese-Australians, emulating the Young Muslim Campaigning Fellowship (a partnership between the Islamic Council of Victoria and Democracy in Colour).

- The Commonwealth Government should establish a national integrity commission to address the issue of undue political influence that has now become tied to Chinese-Australians.

- The Commonwealth Parliament should pass laws that cap political donations to help rebuild the public’s trust in our political institutions.

Author

Osmond Chiu is a Research Fellow at the Per Capita think tank. He has worked in policy roles for over a decade and has written for Guardian Australia, Sydney Morning Herald and Canberra Times. He is the chair of the Inner West Council Multicultural Advisory Committee and also an elected rank-and-file member of the NSW Labor State Policy Forum.

China Matters does not have an institutional view; the views expressed here are the author’s.

This policy brief is published in the interests of advancing a mature discussion on culturally diverse representation of Australia’s political institutions. Our goal is to influence government and relevant business, educational and nongovernmental sectors on this and other critical policy issues.

China Matters is grateful to four anonymous reviewers who received a blinded draft text and provided comments. We welcome alternative views and recommendations, and will publish them on our website. Please send them to [email protected]

Notes

- “Diversity milestone’ as one in ten now from an ethnic minority background.” (2019, December 13). British Future. http://www.britishfuture.org/articles/britain-elects-diverse-parliament-ever/

- Griffith, A. (2019, November 5). “House of Commons becoming more reflective of diverse population.” Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/november-2019/house-of-commons-becoming-more-reflective-of-diverse-population/

- Farrar, D. (2017, October 9). “The 52nd New Zealand Parliament demographics.” Kiwiblog.

https://www.kiwiblog.co.nz/2017/10/the_52nd_new_zealand_parliament_demographics.html - Blakkarly, J. (2019, May 21). “Australia’s new parliament is no more multicultural than the last one.” SBS News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/australia-s-new-parliament-is-no-more-multicultural-than-the-last-one

- Biddle, N., Gray, M., Herz, D. and Lo, J. (2019). Research Note: Asian-Australian experiences of discrimination. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods

- Seo, B. (2019, May 13). “As money dries, Chinese-Australians organise.” Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/as-money-dries-chinese-australians-organise-20190508-p51lap

- Lewis, A. (2019, January). “The way in: Representation in the Australian parliament.” Per Capita. https://percapita.org.au/our_work/the-way-in-representation-in-the-australian-parliament/

- AAP (2019, 21 August). “People from culturally diverse backgrounds ‘crucial to Liberal party’s future.” SBS News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/people-from-culturally-diverse-backgrounds-crucial-to-liberal-party-s-future

- Milione, S., (2019). “A truly representative democracy – Increasing the representation of Indigenous and culturally diverse women in Australian politics.” Emily’s List.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 census quickstats: Greater Sydney. (n.d.). Retrieved 9 January 2020, from https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/1GSYD?opendocument

- Kang, WC., Sheppard. J., Snagovsky, F., and Biddle, N. (2019). Candidate gender, partisanship and electoral context in Australia. Manuscript submitted for publication. School of Politics and International Relations, Centre for Social Research and Methods. Australian National University Canberra.

- Hartcher, P. (2019, November). “Red Flag: Waking Up to Chinas Challenge.” Quarterly Essay.

- Bagshaw, E. (2019, April 28). “Key Labor candidate says Parliament needs ethnic diversity targets.” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/key-labor-candidate-says-parliament-needs-ethnic-diversity-targets-20190423-p51geh.html