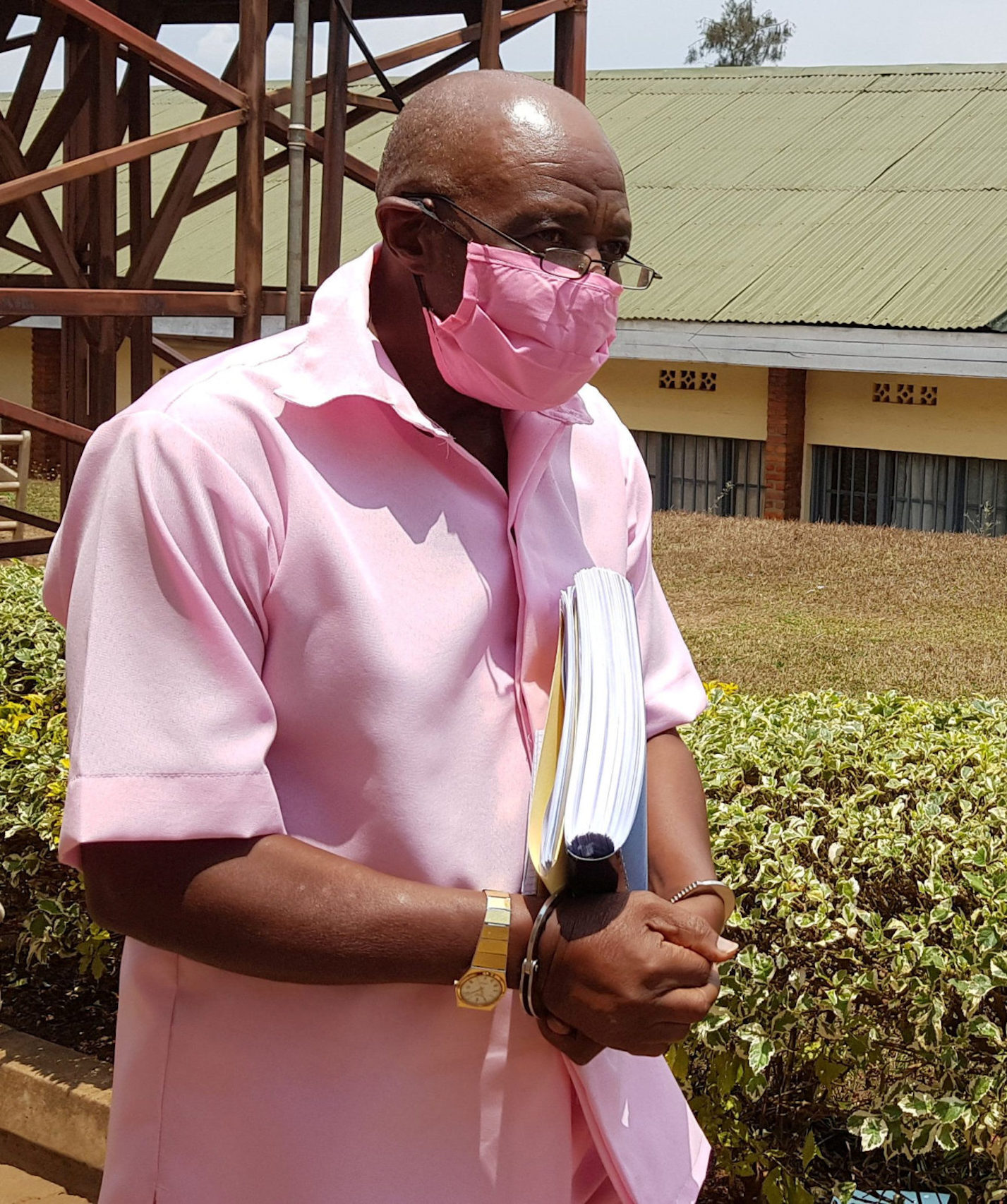

© Photo by REUTERS/Clement Uwiringiyimana

Rwandan activist and former hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who inspired the movie ‘Hotel Rwanda,’ has been convicted of terrorist offences and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

His conviction lacked sufficient guarantees of fairness required by international and African standards and should not be relied upon. Mr. Rusesabagina’s sentencing also follows allegations that the Rwandan authorities targeted his lawyer’s and his daughter’s phone using the ‘Pegasus’ surveillance tool.

The ABA Center for Human Rights monitored the proceedings against Mr. Rusesabagina and the twenty co-accused tried alongside him over the course of the past year as part of the Clooney Foundation for Justice’s TrialWatch initiative. Mr. Rusesabagina, a 67-year old cancer survivor with high blood pressure, now faces the prospect of years in a prison system that, according to his lawyers, has subjected to him mistreatment. He has also missed two cancer screenings and the prison authorities have denied him access to prescription medicine provided by his Belgian doctor.

A recent TrialWatch report by Geoffrey Robertson QC and ABA Center for Human Rights staff concluded that Mr. Rusesabagina’s trial entailed severe violations of his fair trial rights and had the hallmarks of a “judicial spectacle.” Among other procedural flaws, the Rwandan authorities violated Mr. Rusesabagina’s right to confidential communication with a lawyer, his right to adequate facilities to prepare for trial, and his right to the presumption of innocence.

“This was a show trial, rather than a fair judicial inquiry,” said Geoffrey Robertson QC, the Clooney Foundation for Justice’s TrialWatch expert on the case. “The prosecution evidence against him was unveiled but not challenged.

“Given Mr. Rusesabagina’s age and poor health, this severe sentence is likely to be a death sentence.”

The court refused to permit cross-examinination of the Bishop who said he tricked Mr. Rusesabagina into getting on the plane that took him to Rwanda. Later, after Mr. Rusesabagina had withdrawn from the trial, the court did not question the credibility of two key prosecution witnesses, despite the fact that one of them had worked for the Rwandan government and the other had previously testified against government opponents. Before and during the trial, Rwandan President Paul Kagame repeatedly suggested Mr. Rusesabagina was guilty without waiting for a verdict, saying that he had “the blood of Rwandans on his hands.” Taken together, this raises serious concerns about the fairness of the proceedings.

Further, the court seemed uninterested in key questions regarding how the FLN (National Liberation Front), an armed group alleged to have perpetrated deadly attacks in Rwanda, and the MRCD – a group of political parties with which Mr. Rusesabagina was involved – were connected. Instead, the court referred repeatedly to the “MRCD-FLN,” seeming to accept at the outset the prosecution’s argument that they were inextricably intertwined. The court also didn’t react when several defendants alleged that records of their interrogations were inaccurate.

Finally, the court coached at least one of the civil parties claiming damages, telling him that they knew what he was saying was wrong because he had previously been in the judge’s office to discuss his damages claim, indicating the judge had pre-vetted what the witness was going to say.

Background

Mr. Rusesabagina’s name is forever linked to the film ‘Hotel Rwanda,’ which dramatized his actions to save lives during the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Since then, he has been a prominent critic of the Rwandan government.

Mr. Rusesabagina disappeared from Dubai on August 27, 2020. On August 31, 2020, the Rwanda Investigation Bureau announced that Mr. Rusesabagina was in its custody. According to his testimony, Bishop Constantin Niyomwungere convinced Mr. Rusesabagina to get on a plane secretly paid for by the Government of Rwanda. Mr. Niyomwungere explained to the court that he told Mr. Rusesabagina the plane was going to Burundi, where Mr. Rusesabagina said he had been invited to speak at local churches. The Bishop also told the court that he had asked the Rwandan authorities whether he could “do something that will allow this killer to be arrested.”

Mr. Rusesabagina was first detained incommunicado and later without access to a lawyer of his choice. During this time, he was interrogated by the authorities. Even when Mr. Rusesabagina did obtain access to his lawyer, the authorities repeatedly intercepted confidential communications between Mr. Rusesabagina and counsel, as conceded by the Rwandan government. Notably, some of Mr. Rusesabagina’s co-defendants have retracted statements they made to the authorities about their own involvement in the alleged crimes, saying that they did not have the opportunity to review the statements before signing them, that they were pressured into making the statements, and that the investigators inserted false confessions into their statements—retractions to which the court paid little attention.

At the start of trial, Mr. Rusesabagina’s defense argued that the circumstances of his transfer to Rwanda rendered the proceedings unlawful and deprived the court of jurisdiction to hear the case. Subsequently, the court allowed the Bishop to testify that he had tricked Mr. Rusesabagina into traveling to Rwanda. The court did not require the Bishop to testify under oath and did not permit defense questions. Relying on the Bishop’s statement, the court found that Mr. Rusesabagina had been ‘lured’ and not ‘kidnapped,’ and thus that it could hear the case. Counsel also argued that Mr. Rusesabagina’s trial should be adjourned because he had not been given adequate time and facilities to prepare his defense: among other things, Mr. Rusesabagina had yet to receive access to key documents from the case file. After the court ruled against the defense request for additional time for preparation, Mr. Rusesabagina withdrew from the proceedings.

Following Mr. Rusesabagina’s withdrawal, the court failed to safeguard his rights, as is its obligation under international and African standards. The court, for example, allowed prosecution witnesses to testify without interrogating their credibility and asked leading questions of other witnesses, to the point that it appeared the court itself was trying to build the case against Mr. Rusesabagina. One co-defendant was told: “in your pleading there is nowhere where you talk about Rusesabagina … you should say something about him.” Likewise, another witness had been testifying in his own defense when the court suddenly pivoted to focus on Mr. Rusesabagina, asking: “you said that you heard that it was Rusesabagina who gave funding, that even one day he sent money for the military party. How did you get to know about this?”

A TrialWatch report that covers the judgment and sentence will be made available shortly at www.cfj.org.