‘We are drowning in insecurity’: young people and life after the pandemic

Simply sign up to the Coronavirus economic impact myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This article is the introduction to a series of FT View editorials and daily online debates which make the case for a new deal for the young. Beginning on Monday 26 April with the topic of housing, they will address pensions, jobs, education, the climate and tax over the course of the week. Click to register for the events and see all the other articles

Akin Ogundele did everything right. A born and bred Londoner and the son of immigrants, he worked hard, went to university, found a good job in the financial sector, got married and had children. But at the age of 34, he feels stuck.

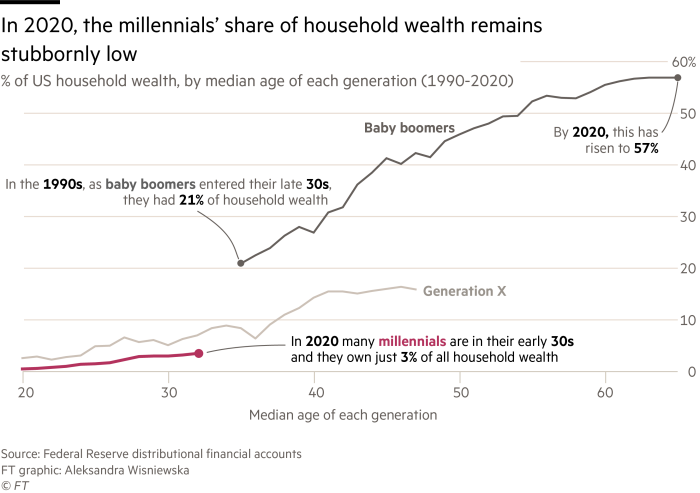

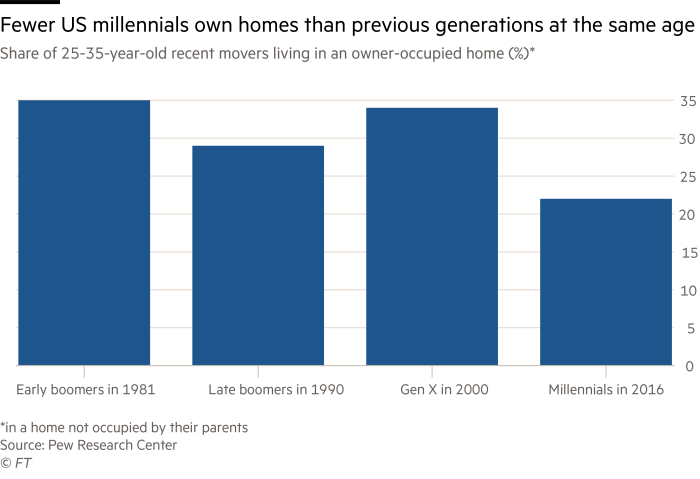

He and his wife and two children live in a rented flat because even with their two salaries they cannot afford to buy in their home city. After decades of accelerating housing costs, the average deposit used to buy a first home in London has risen well above £100,000. Ogundele has seen colleagues buy homes with help from their parents, but he doesn’t have a “bank of mum and dad” and his savings cannot keep up with rising prices.

He worries about the insecurity of renting with his family and the possible damage to their health from living near a main road. But most of all he worries about what assets he will be able to pass on to his children so they don’t end up in the same position.

“If I carry on the way I am, I’m not sure what I’ll be able to pass down,” he says. “It can’t be good for the country — the disparities are just going to grow, the wealthy are going to grow wealthier and those that aren’t will get more and more removed.”

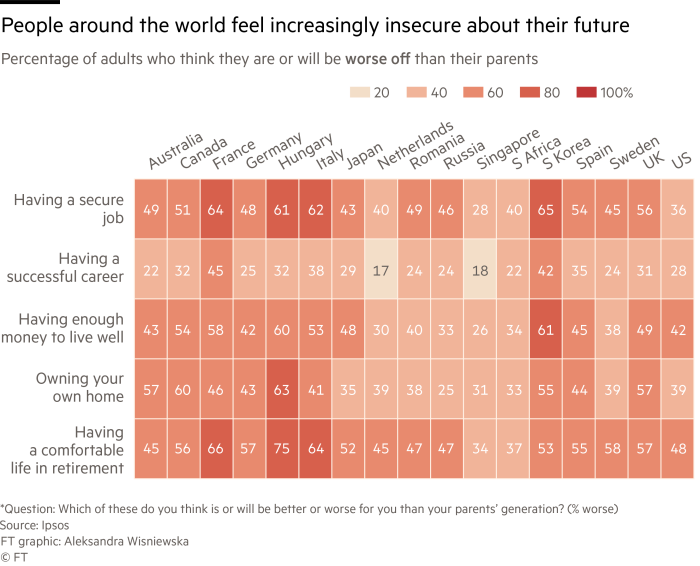

His sense that the social contract has broken for his generation is shared by many young people, and not just in London. When the FT ran a global survey for under 35s about their lives and expectations in the wake of the pandemic, 1,700 young people responded in the space of a week from countries as varied as South Africa, Cambodia, Norway, Australia, Denmark, the US, Portugal, Lebanon, Brazil, Malaysia, India and China.

Many describe feeling as if there is nothing solid under their feet. “Most people my age are paddling so hard just to stay still,” says Tom, an architect. “It’s exhausting — nobody is asking for an easy ride, but all my friends have worked so hard all their lives, and many are losing faith in the system.”

For Killian Mangan, who graduated during the pandemic last year and struggled to find a job, it feels as if “we are drowning in insecurity with no help in sight”. A twenty-something who works for a central bank says: “I sometimes have this feeling that we are edging towards a precipice, or falling in it already.”

This sense of insecurity is changing the way younger generations see the world. The FT’s survey does not claim to be representative, but it hints at shifts in how young people perceive the role of luck versus merit, the way they traverse the world of work, and how they feel about the future.

A 30-something who works in private equity in the UK turns to collateralised debt obligations for a metaphor to describe the position of his generation. “The space I feel I occupy in the sociopolitical order is akin to being the first loss tranche in the debt stack,” he says. “Whenever anything bad happens I have no doubt that, because we lack political and economic clout, we will be left holding the bag.”

Social immobility

Most young people are quick to acknowledge the ways in which their lives are better than those of previous generations. They talk about their educational opportunities, cheaper travel, openness about sexuality and mental health, varied work and the way technology has connected them to the world.

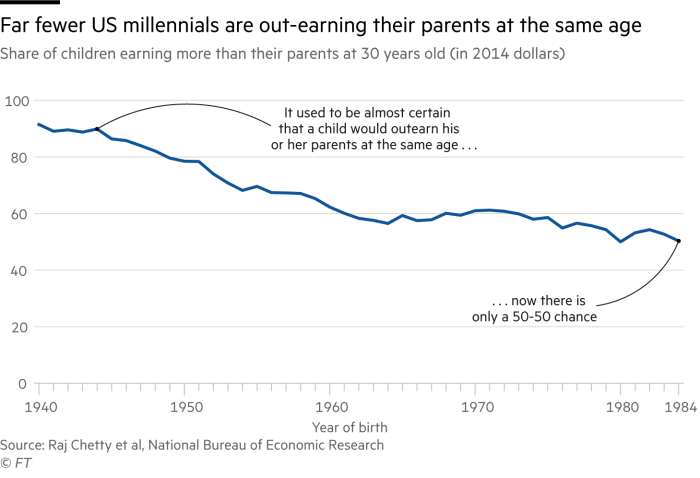

But housing and education have grown more expensive, jobs feel more competitive and insecure, pensions less adequate and the environment imperilled (“my retirement plan is to die in the climate wars,” says one). A large number share Ogundele’s feeling that their parents’ wealth is becoming a more important determinant of their prospects than their own efforts.

FT series: A New Deal for the Young

Join us for a series of live debates this week, every day at 2pm BST, on the following FT View editorials and share your own ideas and questions. Register for free

Monday Housing affordability is a problem in many countries. How can we fix the crisis?

Tuesday How to secure a decent pension for today’s younger generation. A third way is needed.

Wednesday Building better jobs: like every generation before them, young people desire decent, secure employment with prospects.

Thursday A rethink on education: who should pay for university education, and what about those who don’t go?

Friday Young people face a future of environmental destruction. What can be done to fix it?

Saturday Taxing fairly: today’s young face the burden of supporting older generations but benefit much less at the start and end of their working lives.

The statistics suggest they have a point. In the UK, for example, a paper to be published on Monday by the Institute for Fiscal Studies projects that as older generations amass more wealth, average inheritances compared to lifetime income for the 1980s-born will be almost double that of the 1960s-born.

This will damage social mobility. For those born in the 1980s to parents whose wealth levels are in the lowest fifth among their peers, inheritances will increase their lifetime incomes by 5 per cent according to IFS estimates, while those born to parents in the top fifth will enjoy a 29 per cent boost. For those born in the 1960s, the disparity was smaller (2 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively).

“At the moment, while the wealth is still held by older generations it shows up in the data as a difference between generations, but wealth doesn’t disappear, it’s going to flow down and [then] it moves on to being an issue about inequality within younger generations,” says David Sturrock, an IFS senior research economist. “It’s basically saying how much you stand to gain depends on who your parents are and the wealth they have.” Many developed countries share “a lot of the same dynamics”, he adds.

This divide is felt acutely by respondents to the FT’s survey, not just among those on the wrong side of it, but among those on the right side too. “Luckily, for me, I have educated parents who bought a house in London (it wasn’t expensive when they bought it, and is their only asset). But it’s very sad (and colossally unfair) to think that however hard I work, that the wealth of my parents will most likely be the biggest indicator of my future wealth,” writes Ben Alden-Falconer in Margate in southern England. “How is that politically acceptable?”

Many of those who are doing well attribute their success, at least in part, to good fortune. “I am now a director of two successful companies, one start-up and one reasonably sized mineral exploration company. Even with these respectable positions, I wouldn’t have got here without having affluent and supportive grandparents,” says Liam Hardy in Vienna. “It would have been impossible to provide start-up capital or take the time to develop these businesses entirely on my own back.”

Josh from Brighton in England recently quit his job to retrain in computer programming. “I was lucky to be able to take this step and rent out my flat and be supported yet again by my parents,” he says. “Without this possibility many people will be trapped in unfulfilling roles with growing costs of living and limited opportunities to retrain in a fast evolving landscape.”

Perhaps because of this heightened sense of the importance of luck, many say they support policies to combat inequality and help those at the bottom. “I feel a strong desire to be aware of and help those who fell to the bottom leg of the K-curve when the lockdowns began,” says Matthew Arnold in Texas in the US.

Looking for a ladder

In March last year, Stuart started a job at a UK telecoms company on an agency contract. He was given the impression it would be a stepping stone to a permanent job there after 12 months. But last month, he and his agency colleagues got an email inviting them to a conference call. “We knew it was bad news.” About 40 of them were laid off. The 32-year-old, who lives with his parents, says he just wants the chance of a ladder to climb. “If you’re just doing agency work it feels like you’re locked out a bit of the progression, it can make it a lot more difficult to look into the future.”

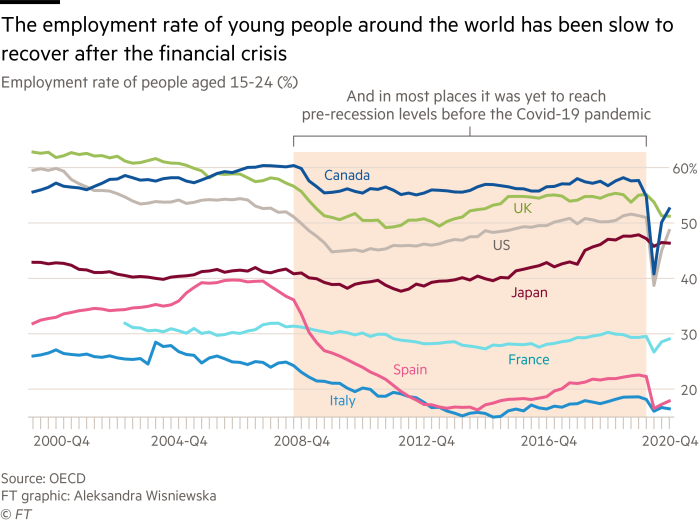

Job insecurity is a common theme among respondents to the FT’s survey, especially among those like Stuart on temporary, fixed-term, agency or zero-hour contracts. Temporary contracts are particularly prevalent for young people in the eurozone: almost half of working 15 to 24-year-olds were on temporary roles on the eve of the pandemic and job losses fell hard on this group.

Many of those who held on to their permanent positions through the pandemic still feel on edge, with a number attributing their unease to their rough ride in the world of work since the 2008 financial crisis.

“I ate spaghetti for a month in 2009 because the company I worked for was owned by a private equity firm, which thought it best to cut me so it could buy out smaller competitors,” says Jim from California in the US. “They eventually hired me back for close to half the pay . . . way to develop talent, right?”

Others talk about the sheer level of competition they perceive for secure jobs. “After 30 or so rejections, I was chosen out of a pool of 2,500 applicants to undergo a psychometric test, followed by a video interview, followed by an assessment centre, followed by a week-long virtual scheme culminating in an interview before being offered a two-year training contract,” says Hadrien, a recent UK graduate. “We are competing with machines and bots, and an ever increasing population of skilled humans,” says another.

This sense of unease, combined with a decade of slow wage growth, student debt and rising house prices, has left a number of young professionals feeling they cannot afford to be patient at work.

“I have what in other generations would be considered a well paying job. But I can barely afford a 2-bedroom flat within commuting distance to raise a family,” says an early 30s communications director in the UK. “So when I’m pushing for pay rises or looking to change jobs for promotion, I am perceived as entitled. Ideally I would love to stay in one role where I can [trust] my company to up my pay. But if I want a family and want a comfortable life, I can’t realistically wait.”

Others are bucking against long working hours in sectors such as law and accountancy, where the cost to one’s health and personal life no longer seems worth the (uncertain) prize.

Have you recently graduated? Tell us about the jobs market

The FT wants to hear from graduates and other young people about their experiences of getting their careers off the ground in these uncertain times. Tell us about your experiences via a short survey.

“The expectations that one responds to emails in the evenings or at weekends, shows up to early (pre-office time) meetings, gives 150 per cent during working hours and puts in overtime to show commitment to the job and the workplace only serve to devalue the work that we do, both metaphorically and literally (in the per-hour rate we receive, which is often calculated as below minimum wage),” says Kira of her time as a junior lawyer in London.

A Shanghai resident in his 20s says China’s explosive economic growth has given him many more opportunities than his parents had, but that house prices are climbing and working conditions worsening. “You might know about 996, which means working from 9am to 9pm for six days a week,” he writes.

Yet there are also many positive stories about the range and variety of work available today. A number of survey respondents say they have found jobs they enjoy, which they had not planned to do or even knew existed when they were at school. “I ended up in a biotech company in the agricultural industry,” says 22-year-old Luca Mariani. “I am extremely happy this has happened . . . I signed up for an AI course ready to learn to code, only to find myself in Cumbria [northern England] learning how to artificially inseminate a cow.”

‘Little hope’

Looking beyond their personal circumstances, many of the FT’s young survey respondents from both developing and developed countries say they worry about the world’s political and environmental trajectory.

When Khalida Abdulrahim was studying business 10 years ago, there was great enthusiasm about “Africa rising; the developing world rising”. But now the 27-year-old Nigerian, who has a job she loves with Google in London, does not feel so optimistic for her home country.

“My parents came of age in an economy full of promise and optimism — they capitalised on that. For me, and many of my generation, the Nigerian economy appears pessimistic and offers little hope,” she says. “Except we look outwards, which is why participating in the global economy, in ways our parents never could, with how much more connected the world is today, could be our saving grace.”

Others talk about corruption in their home countries, instability and democracy in peril. “The older generation does not understand our timidity, insecurity and frustration,” says a 26-year-old from Turkey. A psychologist in Peru says she is “anxious and exhausted”.

Mads Wold, in contrast, knows he lives a good life in Norway. He remembers watching The Wire, the gritty drama set in the US city of Baltimore, then going for a stroll down his pleasant street. “That’s when I was was like, oh shit, I live in a bubble.” But he worries about the global instability that climate change will cause. “One million refugees almost broke European unity; 225m climate refugees will surely annihilate it.”

He is one of a number of young people who say they are not sure whether to have children. “A lot of people my age are having the ethical debate, is it ethically right to have a kid even though you’re not sure if the world will go on? That’s actually a challenge me and my fiancée are having right now,” he writes.

Abhi Kumar, a venture capitalist, says older generations do not “totally grasp the scale of climate change and the worries my generation has in relation to it. For example, I’m from a Global South country [India] and I agonise over permanently emigrating to a place where the effects of climate change won’t be quite as severe when I’m 50-60 years old. I’m not sure older generations quite grasp that anxiety. For them, this is just another challenge that humanity will overcome with a few bruises (like wars, recessions and now pandemics). While I find the optimism endearing in a certain way, it just isn’t grounded in the reality that climate change is going to be a problem like none other we’ve faced as a species.”

Sam, a corporate lawyer from London, captures the feelings of many when she concludes she will be better off than her parents in some ways, but not in others. “I have a professional job and they didn’t. [But] In terms of . . . the full-belly feeling of knowing your children will have a better future than you? Not so much.”

Comments