One year after police killed Stephon Clark in his family’s backyard, law enforcement officials launched a different kind of assault on the 22-year-old.

They attacked his reputation and impugned his character.

The Sacramento district attorney (DA) publicly released a series of Clark’s text messages with his fiancee, detailing conflicts in their relationship and his mental health struggles. Salena Manni, his distraught fiancee, told reporters that what happened days before police killed Clark was irrelevant: “It’s about the officers who murdered him … because he had a cellphone in his hand.”

The DA’s decision this month to publicize Clark’s intimate communications, while announcing she would not charge the officers who killed the unarmed father, stunned the family and activists, who already had little hope they would achieve accountability through the justice system. But the practice of DAs vilifying victims of police violence is not unique to Sacramento.

District attorneys have repeatedly engaged in what victims’ families describe as cruel and painful smears of the dead. In some cases, prosecutors assigned to investigate killings present irrelevant and inaccurate information about victims and their pasts while exonerating the police – a kind of “character assassination” that spreads in the media. The tactic, critics say, emboldens racist policing.

“My son’s life was relegated to falsehoods and accusations,” said Dominic Archibald, recounting the ways prosecutors denigrated her son after he was killed by a California sheriff’s deputy in 2015. “The scary part to me is they perpetuate this idea … that he was a bad person and he should’ve been murdered.”

Some families are fighting to reclaim their loved ones’ reputations while advocating for changes to what reformers see as one of the most powerful and unethical forces of the American criminal justice system.

When prosecutors promote racist tropes

Often under the guise of transparency, DAs now publish detailed reports on the killings that provide an account of what happened, why deadly force was “reasonable” and, in some cases, in-depth background on the deceased. They argue that these facts are necessary for the public to understand their decisions.

But in practice, it means they dredge up negative details about a victim’s life prior to the incident, sometimes in ways that seem designed to promote racist stereotypes and prey on fears.

“The goal is to get the public to not like him,” said L Chris Stewart, a civil rights attorney, citing the kinds of facts DAs typically exploit to smear the dead: claims about criminal records, drug use, gang allegations and missed child support payments.

“It’s hard to justify selectively releasing information that creates a particular image of a victim,” said Daniel Medwed, Northeastern professor of law and criminal justice. “It’s very disturbing.”

The pain of these reports can be immense for families, who in some jurisdictions have to wait years for them, knowing they are very likely to exonerate their loved one’s killer.

In 2016, prosecutors branded Nathaniel Pickett, 29, a violent criminal after his death. He was unarmed when a sheriff’s deputy in San Bernardino county stopped him for a “pedestrian check” and later accused him of “trespassing” at a motel property, where he was in fact living.

Pickett, who lived with mental illness, was “fidgety and could not stand still”, according to the deputy, Kyle Woods, who interrogated him and tried to arrest him, eventually shooting and killing him after a foot chase.

A year later, the district attorney’s office cleared Woods of wrongdoing and released a report with a lengthy section labeled “criminal history”: Pickett had multiple previous cases of resisting arrest and a warrant for failure to appear in court. The report also said he “previously used marijuana”.

“If you’re going to say a person ‘resisted arrest’, tell me what they were being arrested for?” said Archibald, his mother. “You’re sullying my son’s name.”

His rap sheet was documentation of police harassment, she added: “What hurts me is my son was being targeted. He was a tall, dark complexion black male who was profiled.”

The DA’s report also contained falsehoods that misrepresented her son, the mother said.

The prosecutor’s office alleged that Pickett repeatedly “punched” the deputy in its report. But during a civil trial, attorneys for Pickett’s family presented video evidence of the encounter that did not show him throwing any punches, as well as photos of Woods after the incident with no visible injuries.

A jury ruled that Woods had negligently used lethal force and Pickett should never have been detained. But that verdict came last year, long after the DA had presented its own narrative of Pickett as a criminal threat, with claims that were repeated in local media.

In the case of Alton Sterling, killed by Louisiana police outside a convenience store where he had been selling CDs, state prosecutors said the killing was justified in a report that revealed he had drugs in his system and detailed a previous interaction with law enforcement. The release of this information was unwarranted given that the entire encounter and killing was captured on video, said Stewart, the family’s lawyer.

“You are using his past to determine whether the officers were right?” Quinyetta McMillon, the mother of Sterling’s son, said in a recent interview. “This has nothing to do with why he was gunned down.”

The personal attacks on Sterling were painful, she added: “It was very embarrassing … We’re all humans. We all make mistakes. No one is perfect.”

Working with police to criminalize victims

Police in America kill upwards of 1,000 people a year. Officers who kill on duty almost never face criminal charges in the US, where the law broadly shields police who claim they feared for their lives when they pulled the trigger.

The systems vary by state but typically involve locally elected DAs overseeing inquiries into killings by police. This means they are often tasked with investigating members of police departments that they work with on a daily basis. A Guardian analysis found that in 2015, prosecutors in the US cleared police of wrongdoing in 217 cases involving officers in their direct partner agencies. Often, the DAs have received campaign donations from local police unions.

The DA investigations into killings by law enforcement look dramatically different from prosecutors’ traditional homicide inquiries. “The murderer becomes the victim, and the victim becomes the criminal,” said Melina Abdullah, a Black Lives Matter organizer who works with families of those killed by Los Angeles police.

For Latino boys and young men in Los Angeles, vague and unsubstantiated claims of gang affiliations are common, attorneys said.

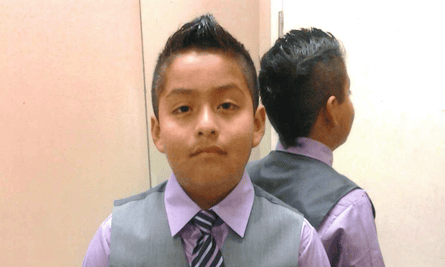

After a Los Angeles police officer chased 14-year-old Jesse Romero down the street and shot him dead, prosecutors released a report that painted the first-year high schooler as a potential “criminal street gang” member who may have been involved in “vandalism”.

“They lied,” said Jesus Romero, Jesse’s father, choking up as he described how he wanted his son to be remembered. “All the community knew him as a good kid, as a friendly kid.”

Witnesses said Jesse had thrown a gun over a fence before he was shot dead.

Speaking in Spanish through a translator, Jesus said his son, like many of the Latino boys in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of LA, had previously been unfairly stopped and searched by police: “They were always harassing him.”

Publishing a victim’s record, but hiding an officer’s past

Prosecutors who focus on a victim’s past sometimes apply a different standard to the officers they are purportedly investigating. That can mean DA reviews that altogether ignore an officer’s troubling record.

In the report on 14-year-old Jesse, the Los Angeles district attorney, Jackie Lacey, did not mention the fact the officer who killed him, Eden Medina, had killed another man two weeks prior – shooting a man in the back as he lay on the ground.

“How is that a fair assessment of that officer?” said Humberto Guizar, the family’s lawyer, who said he feared that in this current political climate, law enforcement was emboldened to slander victims.

Jesus, Jesse’s father, said he couldn’t understand the exclusion of Medina’s record from the DA’s report: “I want the whole world to know.” (The Los Angeles DA’s office declined to comment).

Sometimes, DAs gloss over facts about officers that seem directly pertinent to the case.

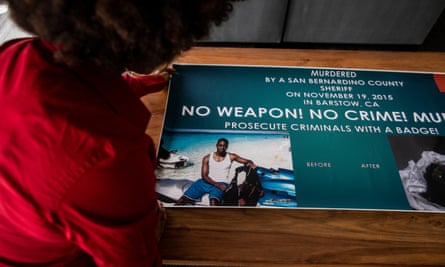

Police killed Diante Yarber, a 26-year-old father of three, with a barrage of bullets fired at a Walmart parking lot last year in Barstow, California. He was unarmed and inside his car when he was killed, and the family said it was a clear act of racial profiling.

The San Bernardino county DA’s report announcing no charges against the officers said Yarber was a “gang member known to carry guns and run from law enforcement”.

Yarber was not a gang member, said his family’s attorney Sharon Brunner, adding that the DA’s report exaggerated his criminal record in an attempt to “dirty him up”. What’s more, the DA’s analysis of whether Officer Jimmie Walker should face charges included no discussion of the fact that the officer had previously been charged with a hate crime, accused of yelling racial slurs and attacking a man in 2010. (He eventually pleaded guilty to lesser misdemeanor charges.)

The DA briefly noted Walker’s history, but did not discuss it as a consideration when deciding whether to charge him.

“It’s very, very devastating – emotionally and physically,” said Mary Padilla, the grandmother of one of Yarber’s children. “This officer had a history that wasn’t brought up.”

The San Bernardino DA, Jason Anderson, declined to comment on the Pickett and Yarber cases, which a previous DA oversaw, but he said his reports on police killings would generally include “all facts and circumstances that are relevant to the reasonableness of the officer’s actions” and would publish a victim’s criminal record “if that were going to be relevant, admissible evidence at trial”.

He added: “We never desire to cause harm to anyone’s loved ones.”

Reclaiming a victim’s humanity

Families who want to fight back have few options. Civil trials can uncover falsehoods pushed by a DA and yield monetary damages, but only after a lengthy process.

Loved ones and their attorneys could also potentially file ethics complaints against DAs over the release of negative information, said Medwed. But the professor said it would be very difficult to prove a violation, given that there are few ethical rules that bind DAs.

Kate Levine, assistant professor at St John’s University law school, has argued that the conflict of interest is too great for DAs to investigate their own police partners, and that an outside investigation could go a long way in addressing concerns about DAs being unfair to victims.

In recent years, some cities have also elected a number of more progressive DAs, who have made this issue a priority. The chief prosecutor in Baltimore, Marilyn Mosby, brought charges against officers in the death of Freddie Gray, and a Chicago prosecutor was voted out after widespread criticisms over her handling of the Laquan McDonald case.

But without serious changes to the legal system, victims’ loved ones will continue to be forced to file lawsuits – and do all they can to speak out and reclaim the humanity of those they lost at the hands of the state.

Archibald said that, instead of the criminal image of her son pushed by the DA, she wished the public knew that he was a “humanitarian”, a talented athlete, and someone who loved rap music, Frank Sinatra and Phantom of the Opera.

Jesus said his son Jesse loved basketball and skateboarding, was beloved by his teachers, and wanted to be an engineer: “He was very intelligent.”

Samantha Robledo, mother of Diante Yarber’s eight-year-old daughter, said she didn’t know how she would talk to her daughter in the future if she were to read reports presenting her father as a criminal: “She knows her dad was not a bad person.”

The killing and subsequent destruction of Yarber’s reputation was still difficult to process, she added: “It’s unfair. They hurt a lot of people … We are still not okay. We are still barely coping.”