I’m Still Saying Her Name

Today I remember my friend Cynthia Wesley and the three other girls who died during the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing 57 years ago.

What stands out in my memory of Cynthia Wesley on that afternoon 57 years ago is the moment our eyes met.

It was a fleeting exchange, and yet in that instant I sensed my friend’s kindness and optimism. She was 14, I was 13, and on that warm Friday in mid-September it was possible to set aside thoughts of the cruelty and racial violence roiling our hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. We were just two kids, excited at the start of a late-summer weekend.

“See you Monday,” she said.

I might have forgotten those words and our brief moment of connection had they not been stamped into my memory by the events that unfolded two days later. Cynthia was one of the four Black girls who died on this day in 1963, when an act of hate shattered the 16th Street Baptist Church. I was with my parents at our own church, Sixth Avenue Baptist, a mile away, when we first heard news that our sister congregation had been bombed.

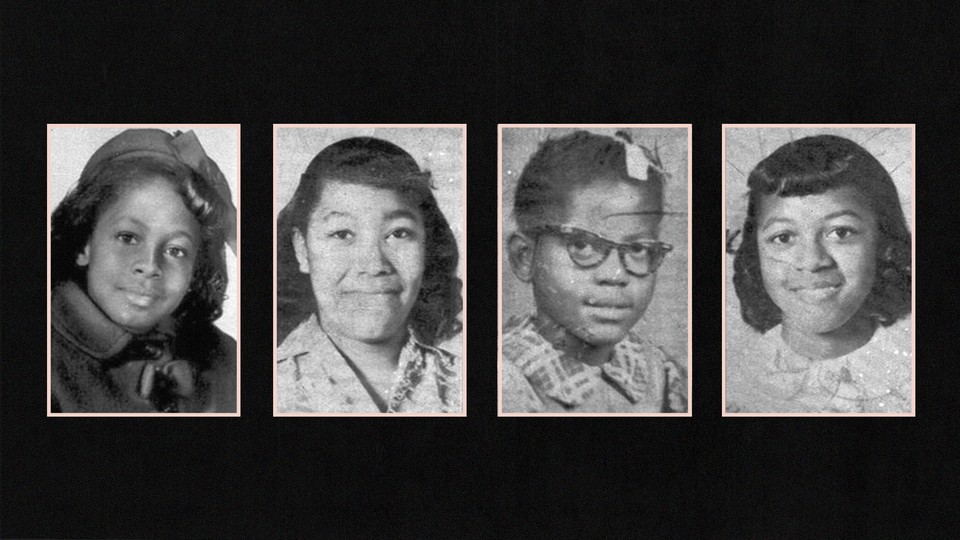

Only later did we learn the names of the four girls who were murdered: Denise McNair. Carole Robertson. Addie Mae Collins. And Cynthia Wesley, my friend.

Just as today we say the names of the many who have been unjustly killed by police officers, the names of those four girls became part of the call for change that energized social protests in the 1960s. In time, a shift in public sentiment compelled lawmakers to take action, and they passed legislation that strengthened voting rights, expanded access to higher education, limited some forms of discrimination, and changed society in countless other ways.

To many who have benefited from those changes, the Birmingham I knew as a child sounds like another planet. Our schools lacked even basic resources. Away from the support and protection of our Black community, we couldn’t go to the movies or eat in most restaurants. Whites Only signs on water fountains and bathroom doors served as constant reminders of our second-class status.

Today, discrimination and racism take different forms. For millions of Black children and their families, and in many communities of color or where poverty is the norm, conditions are equally bleak, and young people are numbed by instability, hopelessness, and the threat of violence.

On many days, the challenges of this period seem overwhelming, and I find myself thinking about what we faced as a society in the ’60s. Months before the church bombing, I was among the hundreds of children who were jailed for marching with Martin Luther King Jr. through the streets of Birmingham in a protest against racism. The long nights in jail were terrifying beyond words, and yet we emerged with hope that the world didn’t have to remain as it was.

Our progress since then has clearly been uneven. I thought society had long moved beyond a point where we would see the authorities lock up innocent children, and yet it’s happening even now at our southern border.

The four girls, and the explosion that killed them, remind us of the best and worst of human nature. Each day, I see photos of their young faces on a poster from Spike Lee’s 1997 documentary, 4 Little Girls. The poster hangs in the family room of my house, and sometimes I pause in front of it and simply wonder, What might they have become? How much potential to love and create was lost on that day?

And then I think about other Black girls, born in the years that followed, who survived and are thriving in this imperfect world.

Kizzmekia Corbett is a National Institutes of Health scientist leading efforts to develop a coronavirus vaccine. Alicia Wilson, the vice president for economic development at Johns Hopkins University, grew up in inner-city Baltimore and is focused on revitalizing the city. Chelsea Pinnix, an associate professor and the director of the radiation-oncology residency program at the University of Texas’s MD Anderson Cancer Center, is improving the treatment of patients with lymphoma. Adrienne Jones, the first woman and the first Black person to serve as the speaker of Maryland’s House of Delegates, is a champion for the state’s children and families.

These four Black women, all graduates of the university where I am president, are amazing role models and leaders. What inspires me in this difficult time is that there are countless others just like them, women and men who have overcome untold challenges to do meaningful work and improve lives.

While thinking about what happened 57 years ago is still painful, I believe that my friend Cynthia, were she alive, would also be inspired by these stories. The message that got us through the 1960s is as true as ever: The world really can be better than it is today. I’ve seen it myself.