It’s strange that we now see America threatened by a plague. Because without plague, America, as we know it, wouldn’t exist.

It may have been the most devastating epidemic in the history of humankind — surpassing in its mortality rates any before or since, including the Black Death in the Europe of the mid-14th century. Smallpox arrived in America with the first Europeans and went on, with several other imported diseases, to wipe out up to 90 percent of the Native population in a relatively short amount of time — millions and maybe tens of millions died.

They were horrible, harrowing deaths. The virus Variola major incubated for two weeks, followed by an intense few days of fever, before the pustules emerged: first in the mouth, throat, and nasal passages, then all over the body, including around the eyes, where they often caused blindness. A human being would struggle for perhaps ten days, covered in these sores, erupting in bloody and pus-filled bumps — and then, with luck, the illness subsided. The sores healed; the pockmarks, highly visible on the face, remained. The residue from these sores was also terribly infectious and lingered on surfaces or cloth for years — but scholars now consider the vast majority of deaths, just like those from COVID-19, to have been from human-to-human transmission.

Much of the terror of this experience is lost to us moderns because a great deal of the death and suffering occurred before Europeans were even able to witness and record it (though, of course, the trauma for the Indigenous reverberated for centuries). But we do know why the toll was so high. Those Native Americans had been the first to discover this continent and, with it, their own sort of American Dream — thousands of years before Europeans imagined theirs. They had first arrived, probably over the Bering Land Bridge connecting Alaska and Russia, around 15,000 years ago, give or take a few millennia, and they found a whole new world, with no humans at all, packed with huge beasts relatively easy to kill with spears, vast prairies, and natural resources that allowed a vibrant hunter-gatherer population to grow as they conquered a virgin continent. It’s not hard to imagine how miraculous this must have felt in the collective memory of these peoples: a long human journey through the bleakest of landscapes into a land of astonishing fecundity — and no human competition.

But because they were often hunter-gatherers, with only a partial reliance on agriculture, they appear to have had little knowledge or experience of plague and no contact with any of the epidemics that had, by then, ravaged Europeans and Eurasians for a few millennia. They domesticated fewer animals and had developed some immunities to many bugs they encountered in their environment.

In this respect, they were blissfully typical of most humans in prehistory. Our species seems never to have experienced epidemic diseases for the vast majority of our time on earth, encountering them only when we settled down, formed stable, concentrated communities, and started farming and domesticating animals for food. Plagues were usually a function of diseases that jumped from precisely those animals in close proximity and spread through concentrations of the human population in settlements, villages, towns, and cities as civilization began. Humans lived in more intimate relations with animals; their settlements compounded filth, infected water, fleas, and excrement human and animal. We were unknowingly creating a petri dish and calling it home.

We are wrong, therefore, to think of plague entirely as a threat to civilization. Plague is an effect of civilization. The waves of sickness through human history in the past 5,000 years (and not before) attest to this, and the outbreaks often became more devastating the bigger the settlements and the greater the agriculture and the more evolved the trade and travel. What made the American plague of the 16th century so brutal was that it met a virgin population with no immunity whatever. The nightmare that humans had been dealing with and adapting to in Europe and Asia for millennia came suddenly to this continent all at once, and the population had no defense at all. The New World became a stage on which all the accumulated viral horrors of the Old World converged.

That’s why we live in a genocidal graveyard. We always have. But if plague was created by mass urban living, and spread through trade and travel, and made much more likely with every new foray into virgin territory, then this story is far from over because those stories, of course, are far from over as well. As the human population reaches an unprecedented peak, as cities grow, as climate change accelerates environmental disruption, and as globalization connects every human with every other one, we have, in fact, created a near-perfect environment for a novel pathogen-level breakout. COVID-19 is just a reminder of that ineluctable fact and that worse outbreaks are almost certain to come. Compared with past epidemics, this one is, mercifully, relatively mild in its viral impact, even though its cultural and political effects may well be huge. Compared with future ones, against which we may also have no immunity at all, it could serve as a harbinger: We could be the next generation to discover a promised land, only to have it taken brutally and terrifyingly away.

Plagues have often been catalyzing events, entering human history like asteroids hitting a planet. They kill shocking numbers of people and leave many more rudderless, coping with massive loss, incalculable grief, and, often, social collapse. They reorder the natural world, at least for a time, as human cities and towns recede and animal life reemerges and microbes evolve and regroup. They suspend a society in midair and traumatize it, taking it out of its regular patterns and intimating new possible futures. In some cases, a society redefines itself. In others, trauma seems the only consequence.

Imagine, for a moment, what confronted the understandably complacent Romans of the second century CE. Out of the blue, their unparalleled civilization was beset by a disease that they had never known before and that began killing people in staggering numbers. For much of Roman history, they had lived in a near-ideal climate: warm, wet, and relatively stable. Trade was growing, wealth was accumulating, and globalization — via trade across the Indian Ocean and new roads connecting all parts of the empire — was reaching a peak. But in 43 BCE, the first climate shock came, as a volcanic eruption from as far away as Alaska prompted a sudden cold spell, and then, during the second and third centuries, a far more variable and colder climate set in, prompting distant animal species, with their own viruses, to move territory, creating new pathways for pathogens to break out of their familiar habitats.

The disease burden among Romans was already high and getting higher, as Kyle Harper has explored in his groundbreaking book The Fate of Rome. Bigger settlements and cities, combined with appalling hygiene (open-cesspool toilets were usually located within the house) and close proximity with domesticated animals, created a network of danger zones. Malaria was a constant, diarrhea ubiquitous; tuberculosis became more common; leprosy arrived and stayed. Some viruses — like Tatera poxvirus and a few of its relatives — were carried by only a single species, such as camels or naked-soled gerbils, but they could jump species in certain circumstances, from animals to humans if any were nearby, and then from human to human.

When the inevitable epidemic arrived, in what was likely a form of smallpox, it was one of the deadliest enemies the Romans had ever faced. Its symptoms were, in Harper’s words, “fever, a black pustular rash, conjunctival irritation, ulceration deep in the windpipe, and black or bloody stools.” The asymptomatic period was about ten days, easily allowing those infected to travel with no one knowing, and death often came within a week or two. By 172 CE, what is now known as the Antonine plague had devastated the Roman military and killed somewhere around one out of every ten people in the Roman Empire. It came and went for at least the better part of a decade, culling the population mercilessly.

Rome staggered on at first, rebuilding and repopulating, and seemed to recover. But as the climate churned, another pathogen wrought havoc, a virus Harper suggests may have been related to Ebola, which caused bloody eyes, a bloody esophagus, and bloody diarrhea. This one hit a society already weakened, and this time, Rome struggled to survive. Mercifully, there was an epidemiological reprieve in the following centuries, allowing some population recovery. But then an extraordinary series of volcanic eruptions in the year 536 shifted the odds again. The volcanic activity was greater than at any point in the past 3,000 years, spewing a massive amount of debris into the atmosphere, clouding the sun for over a year, destroying crops from China to Ireland, and, once again, producing shifts in microbial and animal behavior. Procopius, a Byzantine historian, noted, “For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during this whole year.”

It was likely this sudden weather shift that rebooted human epidemics in the sixth century. Harper notes that volcanic, climate, and weather events affect a whole variety of species. Among them, crucially, are rodents, who may respond by moving out of their accustomed habitat to find warmer or wetter territory, and who naturally carry with them their own viruses and bacteria. A current scholarly hypothesis is that it was probably Chinese marmots, carrying a bacterium called Yersinia pestis, that, in these cold years, moved territory and transferred this pathogen to other rodent populations they interacted with, likely by sharing fleas. Among these new carriers were the enterprising and highly mobile black rats, often called ship rats because of their propensity to follow grain and food across the oceans. Scientists have also discovered a mutation in Y. pestis in just a single protein-coding gene that emerged, they believe, right before the Roman outbreak in the rat population, making the rodent disease suddenly more transmissible via fleas.

And soon enough, those black rats arrived in the Roman port of Alexandria. They carried with them their own parasite, a flea that lived on the rats’ blood and could survive up to six weeks without a host — making it capable of enduring long sea voyages. And as the bacteria spread among the rats, and their population began to collapse, the fleas, desperate for food, sought alternatives. Living very close to the rats, humans were an easy target. Before too long, the bacterium was everywhere, because, once in human blood, it could also be spread via droplets in human breath. For several days after infection, you were asymptomatic, then grotesque black buboes appeared on your body — swollen lymph nodes near where the fleas had bitten. Death often came several days later.

John of Ephesus noted that as people “were looking at each other and talking, they began to totter and fell either in the streets or at home, in harbors, on ships, in churches, and everywhere.” As he traveled in what is now Turkey, he was surrounded by death: “Day by day, we too — like everybody — knocked at the gate to the tomb … We saw desolate and groaning villages and corpses spread out on the earth, with no one to take up [and bury] them.” The population of Constantinople was probably reduced by between 50 and 60 percent. The first onslaught happened so quickly the streets became blocked by corpses, the dead “trodden upon by feet and trampled like spoiled grapes … the corpse which was trampled, sank and was immersed in the pus of those below it,” as John put it.

This must have seemed like the end of the world. For most, there was no other explanation. To have the skies go dark for more than a year, and then to see a hideous disease fell half your family and friends, destroying agriculture, city and town life, and religious practices, was an extraordinary trauma. Even the countryside was afflicted, because the rats could scurry and survive anywhere there was food, and, at the same time, the failed harvests following the year of darkness led to widespread malnutrition, weakening immune systems. Imagine living in a city that, only a couple of years previously, had had twice the population: the empty streets, the vacant houses, the silence, and the near madness of the survivors, stricken with PTSD, crippled by grief, desperate for food.

This time, Rome simply could not recover, its armies laid low by disease, its finances depleted, its borders increasingly insecure, its population cut by half. What have sometimes been disparagingly referred to as the Dark Ages were caused, then, by the construction of an advanced, networked, sophisticated civilization and its subsequent destruction by microbes you couldn’t even see.

This kind of trauma, the historical record shows, changes us. Reminding humans of our mortality, plagues throw up existential questions that can lead to deep cultural shifts. As the first plagues hit Rome, for example, Christians were often blamed, and the cult of Apollo reemerged. But as the viral and bacterial hits kept coming, these plagues proved to be a tipping point in the move from the old gods to a new one. Christianity showed itself able to assuage the existential angst of constant death in a way the old religions couldn’t. Better still, it contained, as Harper notes, a socially useful network “among perfect strangers based on an ethic of sacrificial love.” And the Christian willingness to tend to the sick, even in a plague, impressed others. The plague seemed to force Roman society to shake off old patterns, like paganism, and seek new ones, like Christianity.

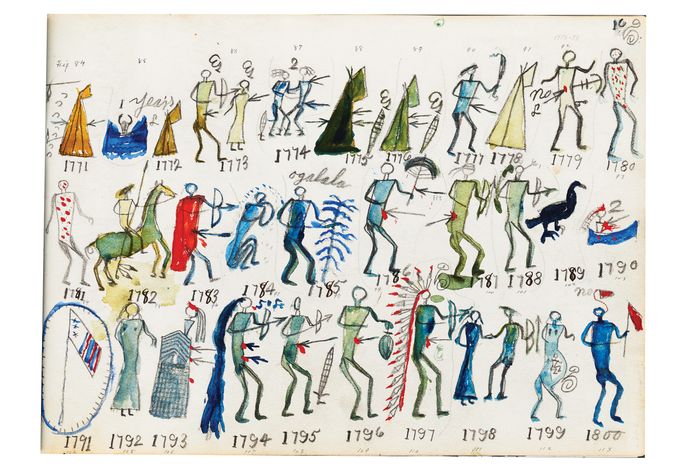

Centuries later, the Native Americans, similarly, saw smallpox as they saw most terrible events: through the prism of their gods and cosmologies. And as the unimaginable toll mounted, and the invaders seemed spared from the worst, many began to see the disease as some kind of proof of their own iniquity or to believe their gods had forsaken them. Their healing ceremonies and rituals, which sometimes included saunas followed by plunges into icy water, failed again and again. In his masterpiece, Plagues and Peoples, William H. McNeill poignantly notes reports of unprecedented suicides in their ranks and even the abandonment of newborns, as Native Americans lost faith in their own civilization and gods.

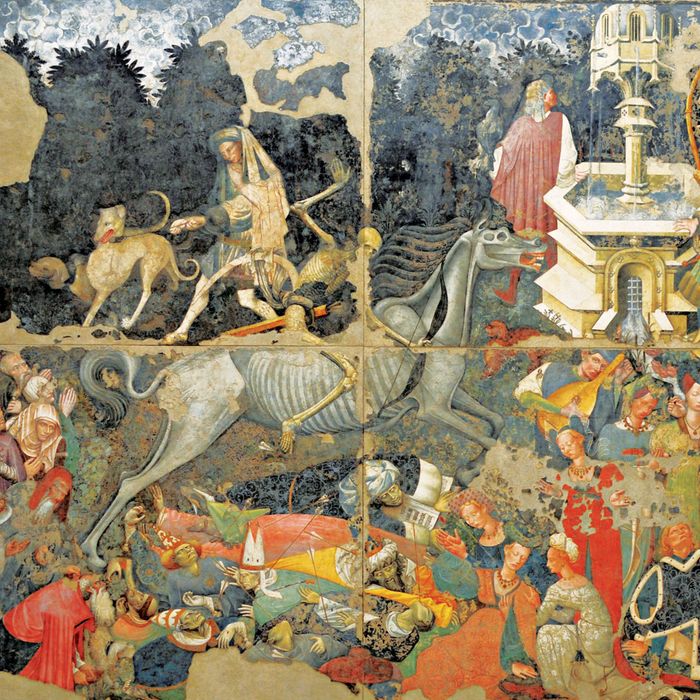

And plagues drive people crazy. You might call them mass-disinhibiting events. It’s not hard to see why. When the plague returned to a fast repopulating Europe in the 14th century, in the Great Mortality known as the Black Death, up to 60 percent of Europeans perished in an astonishingly short amount of time. When normal life has been completely suspended, and when you don’t know if you’ll be alive or dead in a week’s time, people act out.

A cultish sect, which had first arisen earlier in Italy, emerged in Germany, for example, called the flagellants. These half-naked protesters traveled from town to town on foot in pilgrimages, atoning for the sins they believed had caused the plague, and whipping themselves bloody and raw as penance, in bizarre public rituals that drew big crowds. They rejected the established Church, claimed to have direct access to Jesus and Mary, disrupted Masses, and, as time went by, radicalized still further, becoming increasingly populated by the poor and ever more anti-Semitic. Forbidden to take a bath, shave, or change clothing on their pilgrimages, they also doubtless became unwitting spreaders of the disease as they moved from place to place and masses of panicked penitents greeted them.

Jew-hatred, which had been percolating for several centuries, exploded. In the fear and panic of the plague, rumors were started about a Jewish conspiracy to wipe out Christendom. Jews did this by poisoning wells, the slur posited, and in response, pogroms became even more severe than in the past. In Basel, for example, as the writer John Kelly notes in his book The Great Mortality, there was a grotesque prefiguring of the 20th-century Holocaust when a wooden house was built on an island to contain all the Jews in the city, who were then forced into it, locked in, and set aflame as people watched. Jews were bludgeoned to death; they were burned at the stake.

It was as if a plague gave people both an excuse and a license to act out their ugliest impulses. Pope Clement VI issued a bull condemning the violence, making the rather obvious point that “it cannot be true that the Jews … are the cause … of the plague … for [it] afflicts the Jews themselves.” But this was not about reason; it was about scapegoating and a sense that anything was permissible as catastrophe struck.

Plagues do not usually unite societies; they often break them apart in this way. Around the turn of the 20th century, for example, Asian immigrants were blamed for an outbreak of bubonic plague in San Francisco and Honolulu; in 1918, enterprising xenophobes settled on Spain as the source of the new and deadly flu and called it “the Spanish Lady,” to add a soupçon of misogyny. In the polio outbreaks at the beginning of the past century, immigrants from Southern Europe were scapegoated. In general, the wealthy escape from cities in plague times, minorities are blamed, the poor revolt, families are torn apart, and cruelty abounds.

Social class comes to the fore. One estimate of the deaths in 1348–49 found only 27 percent of the fatalities among the wealthy, around 42 to 45 percent among priests, and from 40 to as high as 70 percent among the peasantry. Family members were abandoned in their beds, crime increased, thieves stripped victims of clothes, and people ripped the lead off dead neighbors’ roofs. One cleric, Kelly tells us, became known as William the One-Day Priest because he robbed people for six days and celebrated Mass on the seventh.

Some responded to the outbreak by withdrawing from general society in small groups committed to purer, simpler, more abstemious diets to ward off the disease. Others went in the opposite direction. In the words of the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio, some “maintained that an infallible way to ward off this appalling evil was to drink heavily, enjoy life to the full … gratifying all one’s cravings … and shrug the whole thing off as one enormous joke.” Kelly cites John of Reading, a monk who noted that priests, “forgetful of their profession and rule … lusted after things of the world and the flesh.”

And with a literally existential event taking place all around them, 14th-century Europeans shifted in their spirituality as the Romans had done before them. Just as the sixth-century plague had finished off the old religion of the Roman gods and brought the final triumph of Christianity, so a newly personal and mystical variety of that religion replaced the more institutional one. Sects from the lower classes began to emerge — like the Lollards in England, who rejected key Catholic doctrines and translated the Bible into English. In these rebellious religious subcultures, the seeds of the Reformation were sown.

Paradoxically, the Black Death also reshaped and rebuilt the rural economy to benefit the poor. With half the population suddenly wiped out by bubonic plague, food became plentiful and cheap as soon as the harvests returned, because there were so many fewer mouths to feed, and the price of labor soared because so many workers had perished. Day laborers suddenly had some leverage over the owners of land and exploited it. A manpower shortage also led to innovations. With fewer people on higher wages, for example, the cost of making a book became prohibitive — because it required plenty of scribes and copiers. And so the incentive to invent the printing press was created. Industries like fishing (new methods of curing), shipping (new kinds of ships both bigger and requiring less manpower), and mining (new water pumps) innovated to do more with fewer people. The historian David Herlihy puts it this way: “Plague … broke the Malthusian deadlock … which threatened to hold Europe in its traditional ways for the indefinite future.”

In these two bookends of European plague, in the sixth and then the 14th century, you see two ways in which epidemic disease changed society and culture. In one, the disruption and dislocation of mass disease sent the world into a long de-civilizing process; Roman society was gutted and its empire dissolved into various fiefdoms. In the other, a mass-death event triggered a revival, economic and spiritual, in a kind of cleansing process that restarted European society. They were caused by the same disease. In one case, it brought collapse; in the other, rebirth.

Most accounts of the American Revolution focus, understandably, on military and political developments. What most don’t account for is the role that smallpox played in almost losing the war for the Americans. The virus had never gone away on this continent since the 15th century, had devastated generation after generation of Native Americans, and was a constant threat to the colonies themselves. In the late-18th century, it was still at large — and continued to be spread by troop movements of both the British and the colonists. The British, however, had a clear advantage. Most of their troops had experienced some form of smallpox as children and developed immunity. The Americans — Black, Native, and colonizers — were in contrast largely vulnerable.

As Elizabeth A. Fenn writes in her recent study Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic, 1775–82, in 1776, in an early skirmish in the Revolutionary War in Canada, a few thousand American troops were besieged simultaneously by the virus and the British. In a sudden, chaotic retreat, the Americans sought refuge on a swampy island, Île aux Noix, and met a worse enemy. “Oh the groans of the sick,” an observer reported. “Scarcely a tent upon this Isle but what contains one or more in distress and continually groaning, & calling for relief, but in vain!” Reported another, having witnessed a barn full of men covered in vermin: “One nay two had large maggots, an inch long, Crawl out of their ears.” Still another exclaimed, “My eyes never before beheld such a seen [sic] … nor do I ever desire to see such another — the Lice and Maggots seem to vie with each other, were creeping in Millions over the Victims; the Doctors themselves sick or out of Medicine.” No wonder that in 1776, John Adams was despairing, “The small pox! The small pox! What shall We do with it?”

It was close to impossible for the American troops to gather in large numbers without smallpox running rampant. Quarantining had some impact, but in military retreats or advances, it was impractical. George Washington was worried: “Should it spread,” he wrote to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in late 1775, smallpox would be “very disastrous & fatal to our army and the Country around it.” Washington’s brother worried about the effect on recruitment: “I know the dainger [sic] of the small pox and camp fever is more alarming to many than the dainger they apprehend from the arms of the enemy.” Washington, who had had smallpox as a young man and was immune, eventually decided to oversee an unprecedented campaign to inoculate the entire revolutionary army by inserting small amounts of the virus into the skin to create a much milder illness. After a period of sickness, most recovered and could rejoin the battle with immunity to the plague.

It was arguably the most important military decision Washington ever made, evening the score with the relatively immune British, whose African-American allies, never inoculated, suffered terrible losses. Enslaved Black people were particularly vulnerable. Jefferson would later guess that of the 30,000 enslaved Black Virginians who had joined the British, “about 27,000 died of the small pox and camp fever.”

Most Americans today have little, if any, awareness of the role the epidemic played in the war. And this is another curious fact about some plagues but not others: Some seem to shift society profoundly, while others, however intense, are almost instantly forgotten. This is especially true when an epidemic coincides with war — as it often does.

If the 1918 flu pandemic were to occur today, one 2013 study found, it would kill between 188,000 and 337,000 Americans. The reason the death toll would be so much lower than the 675,000 Americans who actually died is that medicine has improved. Many of those who died endured bacterial co-infections, which are now far more treatable with antibiotics. Globally, somewhere around 100 million human beings perished.

The flu’s symptoms were horrifying. In her book Pandemic 1918, Catharine Arnold notes that “victims collapsed in the streets, hemorrhaging from lungs and nose. Their skin turned dark blue with the characteristic ‘heliotrope cyanosis’ caused by oxygen failure as the lungs filled with pus, and they gasped for breath from ‘air-hunger’ like landed fish.” The nosebleeds were projectile, covering the surroundings with blood. “When their lungs collapsed,” one witness recounted, “air was trapped beneath their skin. As we rolled the dead in winding sheets, their bodies crackled — an awful crackling noise which sounded like Rice Crispies [sic] when you pour milk over them.”

But as the summer of 1918 began in the U.S., relief spread. Maybe it was over. And then, in the fall, confident that a vaccine was imminent, several cities, notably Philadelphia, hosted war-bond parades, with large crowds thronging the streets, as with the massive Black Lives Matter marches today (albeit with fewer masks). In the coming weeks, the city morgue was piling bodies on top of bodies, stacked three deep in the corridors, with no ice and no embalming. The stench was rank. City authorities were reduced to asking people to put their dead loved ones out on the street for collection. The second wave of the flu had arrived, brought in large part by troops returning from Europe.

The Army camps were a circle of hell: In Camp Devens, north of Boston, one young doctor arrived to see 63 young men die on his first day. The 1918 flu took aim at the younger generation, leaving some older people untouched. “The husky male either made a speedy and rather abrupt recovery or was likely to die,” that Camp Devens doctor, helpless in the face of this, reported. The average death toll in the camp was a hundred young men a day, and in the fall, morgues were completely overwhelmed. People stole other people’s caskets, or gravediggers simply emptied corpses out of them into a pit in order to bury others.

A survivor remembered, “From the moment I got up in the morning to when I went to bed at night, I felt a constant sense of fear. We wore gauze masks. We were afraid to kiss each other, to eat with each other, to have contact of any kind. We had no family life, no school life, no church life, no community life. Fear tore people apart.” How on earth, one wonders, has this been forgotten? The truth is the memory was repressed, but, as after the Black Death, people sublimated the internal stress into the pleasure of the moment. The Roaring ’20s didn’t come out of nowhere. In the 1919 Carnival in Rio, the acting out was particularly intense. In her history of the epidemic, Pale Rider, Laura Spinney notes how one Rio reveler recalled, “Carnival began and overnight, customs and modesty became old, obsolete, spectral … Folk started to do things, think things, feel unheard-of and even demonic things.”

And as in Rome, and in revolutionary America, there was a direct military consequence. In 1918, the flu may have hit the malnourished German troops a little harder than the Allies, stymieing what they thought might be a critical advance in the conflict. A few historians suggest the flu was a factor in Germany’s defeat and postwar desolation. President Woodrow Wilson’s possible bout of the same flu in Paris forced him to sit out the peace conference for several days. Upon his return, by some accounts, he appeared weakened, and he ultimately failed to prevent the ruinously exorbitant reparations Germany was obliged to pay.

Wilson himself was apparently so intent on winning the war that he never mentioned the influenza in public. Even when he came down with what might have been the illness himself, he kept mum. This is an American pattern. Wilson seemed to ignore the flu entirely; Reagan ignored AIDS in the early years of its devastation; Trump denied that COVID-19 was a threat until he couldn’t — and even now he is minimizing it to advance a sputtering economic recovery. But the public was hardly defying them. They too preferred denial. Americans focused on victory in Europe and consigned the domestic horror to historical oblivion. Similarly, if you ask young gay men in 2020 about the history of AIDS, a plague that occurred in their own lifetime, you are likely to get platitudes or a blank stare. Some things we simply want to forget.

Katherine Anne Porter, who wrote “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” a story inspired by her own experience surviving the 1918 flu, said something in an interview once that has stuck with me. The flu poleaxed Porter, then a 28-year-old chain-smoking journalist for the Rocky Mountain News, and after a near-death experience, she recovered for the next six months. Her hair turned white, then fell out; hallucinations came and went; she tried to get out of bed and broke her arm; she was told that phlebitis would cripple her for the rest of her life. And yet she lived. And it changed her.

“It just simply divided my life,” she wrote, “cut across it like that. So that everything before that was just getting ready, and after that I was in some strange way altered … It was, I think, the fact that I had really participated in death, that I knew what death was, and had almost experienced it. I had what the Christians call the ‘beatific vision,’ and the Greeks called ‘the happy day’ … Now if you have had that, and survived it, come back from it, you are no longer like other people, and there’s no use deceiving yourself that you are … It took me a long time to realize … that I had my own needs, and that I had to live like me.”

I feel similarly, as a survivor of the first plague in my lifetime, HIV and AIDS. Within the gay world, AIDS was a plague quite similar in its impact to those in the past that afflicted the general population. Yes, men who have sex with men were not the only victims, but they made up a big majority of U.S. cases in the beginning, and they still do. Around 700,000 Americans have died of AIDS, a toll COVID-19 is unlikely to match, and concentrated in a far smaller population. I saw close friends die, nursed the sick, mourned ex-lovers, watched familiar faces grow old in a few months and lie dead in a few more. For more than a decade, gay men and their families were beset with the helplessness that defines a plague: the knowledge that there is no cure, that there is only prudence, luck, or death. But mainly death.

It changed me — and many others — for good. The liberation of surviving an early brush with death is hard to describe, but like Porter, I learned that I had to live — and live like me. Regardless of the crowd, or accepted opinion, or communal loyalty, I was determined as the plague changed me to live my life freely, to say what I think, and to do as I pleased. And this is not entirely unusual. Plagues can first depress you, force you to isolate and hunker down. But, in time, they can also prompt a kind of defiance, a very human desire to tell this virus to go to hell and to act in ways that ignore it. Gay men slowly began to try to have sex again and to celebrate the life that sex gave, even as they also always risked, to a greater or lesser extent, illness and death. Over time, as treatments improved and the illness ceased to be a death sentence, condoms, like today’s COVID masks, came to be used sporadically, then less and less, until they were largely cast aside.

There lingered, though, the gnawing sense that those of us who survived had to do something to make the staggering number of victims mean something, to honor them and remember them in some way. It was an extraordinary act of collective will that, out of the ashes of a plague, galvanized the many gay men and lesbians who were determined to remake the world in its wake, to insist on formal civic equality and that they be treated with dignity and respect. And within just a couple of decades, we had achieved this — even the right to marry.

It would never have happened so quickly, or at all, without AIDS and how it illuminated the unique stigma homosexuals lived under. In some ways, in fact, the gay-rights movement of the 1990s and 2000s is best understood as a subplot in the narrative of plague. It sounded crazy to talk of marriage equality in 1989, but plagues, as I’ve noted, make people crazy. The psychological strain, the fear, the anxiety: They build and build until people give themselves permission to scream, to protest, to re-create or reinvent religion, to express themselves fearlessly in public, to reorder the whole.

The extraordinary and near-spontaneous mass gatherings to protest police violence against Black people this year, I suspect, are rooted in this same human need. Untethered from normal routines, indeed from work itself, and shut inside with almost no human contact for months, people needed to vent, to transcend the moment and be with one another. The spark, the killing of George Floyd, was not exactly plague related, but, as sometimes in history, disinhibited feelings of very different kinds can still merge into a collective spasm. And in this plague, Black people have been disproportionately hit everywhere, in large part the result of the familiar burdens of entrenched poverty and discrimination. It seemed to make some kind of sense, in a world remade by plague, to tackle this injustice more squarely and radically than before.

Plagues, in this way, always present the survivors with a choice. Do we go back to where we were, if that is even possible, or do we somehow reinvent ourselves for a new future? The conflicting desires compete in our minds: to go back to normal or to seize the opportunity to change a society temporarily in flux. We can choose to make a different world, reordering our social compact and our political institutions and our relationship to the natural environment in ways that will protect us against, or at least mitigate the damage from, future plagues. Or we can recognize what was precious in what the plague took from us and seek to restore the status quo ante.

This plague comes, as the Roman plagues did, in a period of great climate change, and of near-peak globalization, which almost certainly means more epidemics are on their way. And it has already set precedents that imply a very different trajectory ahead. In the U.S., the federal relief has been extraordinarily generous by American standards, foreshadowing, perhaps, a debt-funded universal basic income and a big redistribution of wealth in the near future. The virus has also proved itself capable of finally cracking the cult of Trump. The president’s inability even to fake interest in or competence over the epidemic may well have made his reelection impossible, and his terrible tone in response to massive protests has rattled even his closest allies. The epidemic hasn’t ended polarization and may even have intensified it. But it has empowered the opposition in ways previously unimagined. And it may have tilted the balance sufficiently, at least in the short term, that once-inconceivable political change could take place here, in what seemed until just a few months ago an impossibly divided and politically sclerotic country.

In this respect, perhaps, COVID-19 in America may best resemble the bubonic-plague outbreak in London in 1665. It devastated the city that summer, prompting an exodus of the wealthy and connected, with perhaps 100,000 eventually dying in a city whose population was just under half a million. Worse, it was followed the next year by the Great Fire of London, which effectively razed the heart of the city, ruining many in the merchant class. But this catastrophe was subsequently seen as a chance to rebuild and renew, and many of the greatest landmarks of London were then constructed, as streets were widened, stone replaced wood, and the economy took off again. The pestilence and fire jump-started a revival not just in the economy and public health but also in the sciences and arts.

You can see the potential contours of a similar response today. This plague makes a strong argument for a more aggressive approach to public health, which would mean, at a minimum, extending health insurance to everyone in the country, as well as reform and renewal for the disgraced CDC and WHO. It could unleash a new wave of infrastructure spending to repair the immense damage to the economy. It could, and absolutely should, end the argument over preventing climate change — because it is so deeply connected to new viral outbreaks, as shifts to hotter weather portend a highly dangerous upheaval in the animal and microbial worlds. And while I worry that this plague could well usher in a new era in which traditional liberalism gives way to a freshly invigorated collective leftism, particularly around identity politics, it could also deeply wound the appeal of the populist right in America, which, once in government, failed the core test of preventing an open-ended, lengthy period of infection, sickness, and death.

Some existing trends might also intensify. It’s hard to see how a policy of mass immigration or free trade will survive public scrutiny for long in a world where viruses cross borders with such surpassing ease. The U.S.-China relationship, already tense, could deteriorate still further. Living online, with all the isolation and depression and extremism that can generate, is now an even stronger and widespread norm, as we avoid physical interaction even more than we did previously. Same with working from home: The atomization of our culture, the already increasing levels of depression, loneliness, and antisocial behavior could deepen further. The collapse of small retail has been accelerated, and the power of the giant tech companies is ever greater. And the epidemic has not assuaged the yawning gap between rich and poor. While COVID relief has made a real, temporary impact, the stark social and economic inequality in the country looms as large as ever. Rates of suicide, drug abuse, and overdosing could climb even higher.

And the deeper reasons for our viral vulnerability have not gone away. Just as plague arrived with civilization, so our unprecedented 21st-century global civilization has made plague both more likely and more dangerous. We have opened up viral pathways in far more places than the Romans ever dreamed of and created transportation networks of unprecedented speed and dynamism across the entire world. Our unstoppable global economic engine, along with climate change, has prompted mass migration from the Global South to the Global North, the kind of disruption we know makes epidemics more likely. We have penetrated the rain forest and unfrozen the tundra; we are releasing long-buried pathogens whose impact on humans we simply cannot even guess at. We have disturbed the planet in precisely the ways that led to devastating consequences for humans in the past. But more so than ever before. Just in the past few years: Ebola, MERS, SARS, and COVID-19.

And we are not in control. If you are still complacent that human science and technology have removed the potential for the mass extinction of humans, you should wake up. We have lucked out so far. COVID-19 is extremely transmissible but not that fatal to most people, all things considered. But even those countries that are success stories didn’t see it coming in the first place and have experienced resilient breakouts. We still have no vaccine — it may be a year or more before we get one, and we do not know how effective it will be. Imagine the next pandemic pathogen as something as devastating as Ebola and as contagious as the flu. We are as defenseless as we have ever been. This relatively mild virus shut the entire world down for a couple of months. What happens when a much worse one shuts it down for longer?

Knowledge of a brutal new virus does not prevent its spread. Only a much more profound reorientation of humankind will lower the odds: moving out of cities, curtailing global travel, ending carbon energy, mask wearing in public as a permanent feature of our lives. We either do this to lower the odds of mass death or let nature do what it does — eventually so winnowing the human stock that we are no longer a threat to the planet we live on.

That’s the sobering long view. It is hard to look at the history of plagues without reflecting on the fact that civilizations created them and that our shift from our hunter-gatherer origins into a world of globally connected city-dwelling masses has always had a time bomb attached to it. It has already gone off a few times in the past few thousand years, and we have somehow rebounded, but not without long periods, as in post-Roman Europe, of civilizational collapse. But our civilization is far bigger than Rome’s ever was: truly global and, in many ways, too big to fail. And the time bomb is still there — and its future impact could be far greater than in the past. In the strange silence of this plague, if you listen hard, you can still hear it ticking.

*This article appears in the July 20, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!