Democratic-leaning parts of the country are not the only losers in President Trump’s anti-immigrant scheme to hijack the census.

His administration’s recent moves to speed up the count appear aimed at making sure Trump is still president when the Bureau’s most important task — providing the data that decides how many House seats each state gets — is finished. In doing so, Trump is also throwing under the bus rural parts of the country, census experts and demographers tell TPM.

The gambit puts at risk for rural regions not just their political representation, but their share of the $1.5 trillion in government funding that is doled out by using census data.

While immigrant communities and dense urban areas will suffer the most in a rushed census count, rural areas too face a serious threat of being undercounted.

“The people who are missing and hard to count are not just typical Democratic voters,” Sunshine Hillygus, a Duke University professor who has served on the Census Scientific Advisory Committee, told TPM. “Rural communities — and frankly Republican states — are very much at risk, not only of losing federal funding, but also of potentially losing out when it comes to representation.”

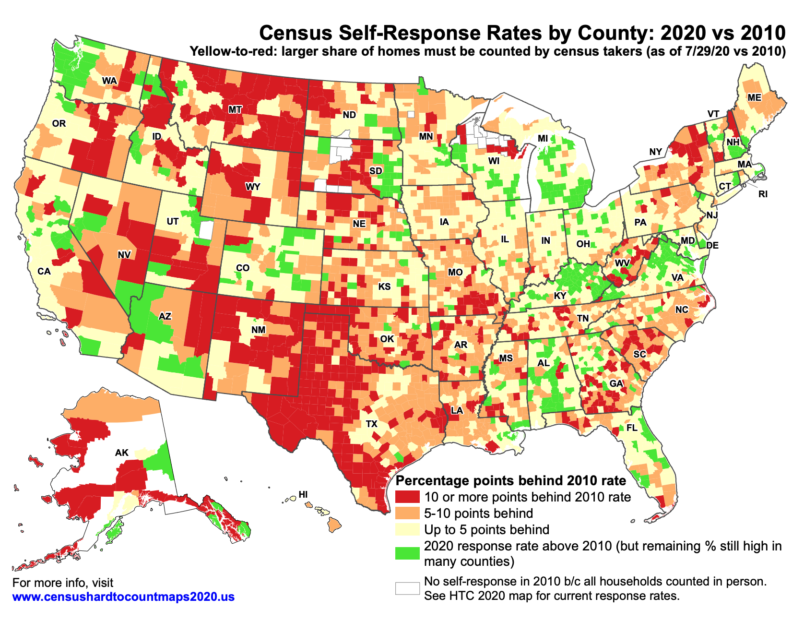

States like Alaska, West Virginia, Maine and Montana —which all are at least partially represented by Republicans in Congress — have had some of the lowest census participation rates in the country so far, and they lag 5 to 10 percentage points behind the national response average.

“Only a quarter of nonmetropolitan counties have met or exceeded that response rate, while more than half of metropolitan counties have,” the Daily Yoder, a news platform operated by the Center for Rural Studies, said in an analysis Sunday.

While based on sheer numbers, urban areas stand to lose the most in an undercount, the best way to understand the disparities is suburban vs rural and urban, rather than red vs. blue, experts told TPM.

A ‘Stark Picture’ Of Who Will Be Impacted By Census Shortcutting Its Door Knocking

The Trump administration’s recent actions on the decennial census are ringing alarm bells for stakeholders, who were already concerned about the steep challenges the pandemic poses to the count.

Several in-person activities were postponed for many weeks, as the coronavirus outbreak scrambled the formal launch of the census this spring. The Bureau had initially reworked its operational timeline to give itself extra time to make up for those delays. The administration is now scaling back that plan in order to deliver the apportionment data on its original due date, as mandated by Congress, at the end of the year.

That means key steps in the process — like sending in-person enumerators to households that haven’t responded to the survey on their own — are being truncated by several weeks.

The larger goal of this expedited timeline, many believe, is to make sure that if Trump loses the election, the Bureau is delivering congressional apportionment data at the tail end of his first term rather than early in Joe Biden’s first term. That would allow Trump to implement his recently-announced policy of excluding undocumented immigrants from the count (assuming it isn’t otherwise blocked by courts.).

Regardless, those efforts to rush the count, which were first reported by NPR, come as the average national self-response is below the self-response rate from the 2010 census.

“Now, there will be a greater share of housing units than there was in 2010, that will need to be enumerated in person,” said Steven Romalewski, the director of CUNY Mapping Service, who has been tracking census response rates.

He told TPM that, in places where the self-response lag is 5-10 percentage points behind where it was in 2010, “it really paints a stark picture of the disproportionate impact of shortcutting the nonresponse follow up.”

In a statement Monday evening announcing the condensed counting timeline, Census Director Steve Dillingham said that under the expedited plan, the Bureau “intends to meet a similar level of household responses as collected in prior censuses, including outreach to hard-to-count communities.”

Poverty and The ‘Trust Question’

Research has shown that different types of households have different reasons for not filling out their census form, according to Jennifer Van Hook, a demography professor at Penn State.

Poverty tends to lower participation rates, she said, as does having a distrust of government or otherwise lacking enthusiasm for communal-oriented initiatives.

Pointing to the low response rates in states like Montana and West Virginia, she said, “that could be about poverty, but it could also be about this trust question.”

Large to very large cities have had the lowest self response rates overall, and the lack of participation is particularly deep in communities of color, according to CUNY’s research.

But the communities with the next lowest response rates are the small towns and unincorporated areas outside of metropolitan areas, which aren’t keeping up with their counterparts in the suburbs.

Similar dynamics are at play when you look out how much lower an area’s current self- response rate compares to where their self-response rates were at the end of the 2010 census.

Part of the reason these regions are behind, according to Romalewski, is because of the way COVID has impacted the Bureau’s so-called “updated leave” program. While the vast majority of households initially receive their census forms in the mail, households in particularly rural or remote areas — including tribal areas — don’t have reliable enough postal service for that outreach. So the Bureau instead sends workers to physically drop off those forms.

The program was delayed due to the outbreak, while it was eventually phased back in, those areas that are covered by it still have some of the lowest response rates.

“Those areas will need even more door-to-door enumeration to make sure they’re counting,” Romalewski said.

Shortchanging the follow-up activities will only exacerbate these disparities, researchers said, and the cuts in the Bureau’s operations will be felt particularly hard in red states that have done little to supplement the federal government’s census operations.

When households don’t respond to the survey on their own, the Bureau uses other approaches to get them counted. In-person numerators are sent to knock on doors. Sometimes, existing government records are sufficient to fill in the count if those initial in-person efforts don’t elicit a response. If the records aren’t adequate, then enumerators may ask neighbors, landlords or other so-called “proxies” the details of who is living in the households.

Existing government records will be less likely to fill the gaps for rural households than other types of communities, according to Hillygus, and depending on proxies also has its shortcomings.

“Proxy respondents are notoriously bad at estimating people in households and their characteristics,” Hillygus said. “You can imagine for both rural communities and immigrant communities, that is even more the case.”