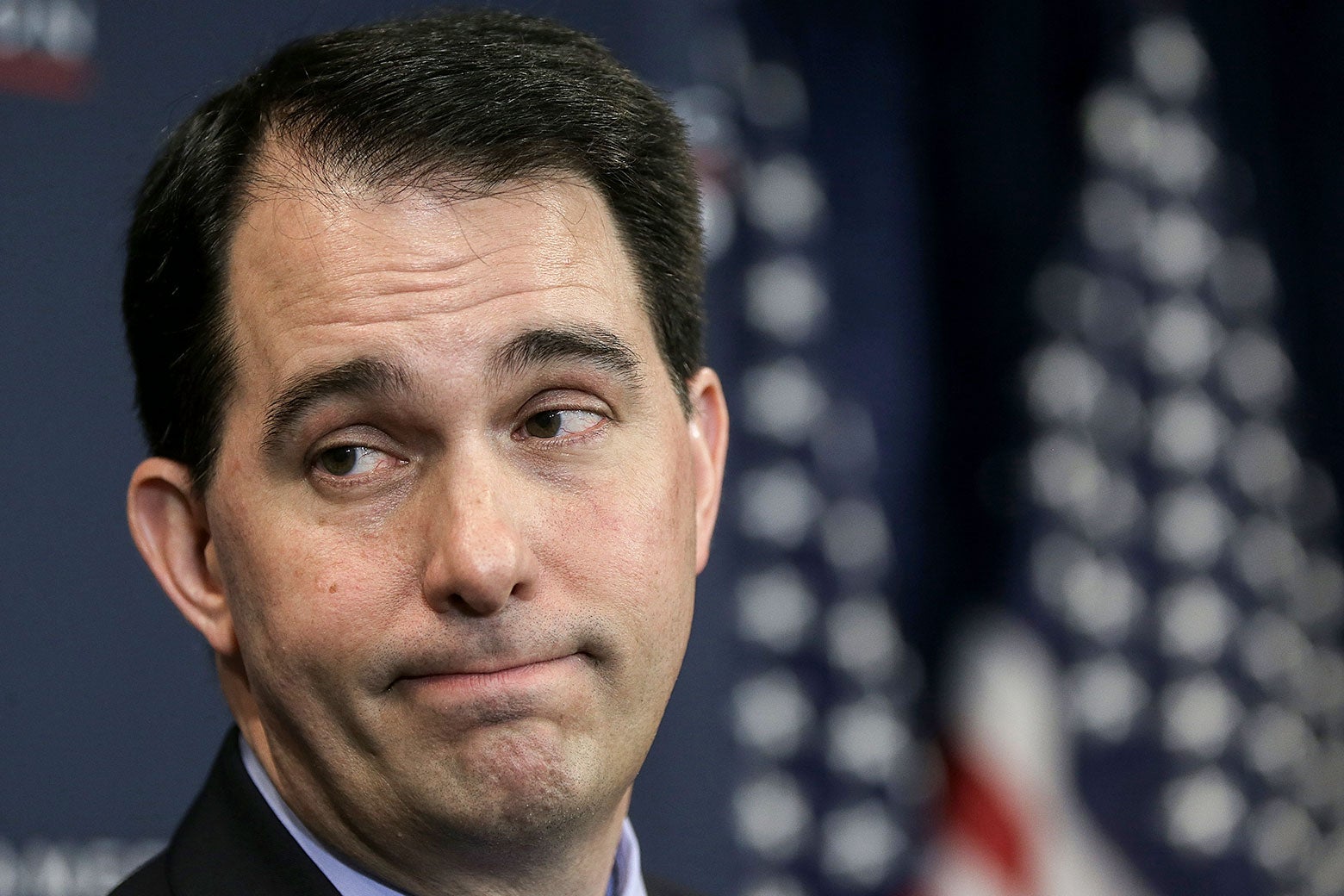

The tumultuous, eight-year tenure of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker will be remembered for his multiyear battle with the state’s public-sector unions, which he decimated with his 2011 “Budget Repair Bill,” known as Act 10. The law stripped public employees of almost all meaningful collective bargaining power, forced leaders to engage in resource-draining annual certification elections, and required most public employees to pay more toward health insurance and pensions, resulting in a drop in take-home pay of 8 to 10 percent. (Police and firefighters were exempted from most of those provisions.) Union membership cratered. This year, every Democratic challenger for governor pledged to repeal Act 10.

So on Tuesday night, it was tempting to see Walker’s downfall as a triumphant return of Midwestern union power—especially alongside the winning gubernatorial campaigns of Democrats in Illinois and Michigan. The Chicago Sun-Times, for example, cheered the defeat of “organized labor’s Public Enemy No. 1.” To complete the narrative, Walker even lost to Tony Evers—a former teacher and the state school chief. But if the results on Tuesday are a referendum on Walker’s career-making moment, it’s much less about Walker’s headline issue—organized labor—than what lies just behind it: education.

Not just because Evers only won by 30,000 votes, a far lower margin than that of the state’s Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin. (In her own race, Baldwin defeated Leah Vukmir, a state senator who sits on the board of directors of the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Koch-backed group that with Vukmir’s help sent a handful of boilerplate conservative laws through the state Legislature.) And not just because Evers actually didn’t draw such a hard line on Act 10, saying he was open to a “compromise” that restored bargaining rights but maintained Walker’s worker payments. More because Walker was tested more explicitly on the union question in a 2012 recall election and again in 2014—and won handily both times.

But if the unions on their own couldn’t defeat Walker, the broader education issue definitely did. More than 2 in 3 ads in support of either candidate were about education this year. Shunning the tone of the landmark union protests of 2011 (and breaking with a dramatic teachers movement in other GOP-run states) in favor of a quieter “local and grassroots” approach, education advocates in Wisconsin went after budget cuts, vouchers, inequality, and teacher shortages. On Tuesday in Madison, a liberal bastion and the home of the beleaguered University of Wisconsin, voter turnout reached an astounding 93 percent.

Walker had tried to counter; he touted (falsely) a “record investment” in schools. But coming from a guy who asserted his foreign policy chops by comparing protesting middle school teachers to “radical Islamic terrorists,” the notion that Walker was the “education governor” was a bit of a stretch.

That Evers is the state school superintendent only heightened the contrast. Mandela Barnes, the lieutenant governor–elect (and the soon-to-be highest-ranking black official in Wisconsin history), summed up the Democratic platform in a victory speech: “We are bringing education back to the state of Wisconsin. We are bringing science back to the state of Wisconsin. And we are going to bring equality back to the state of Wisconsin.”

Walker did cut $800 million out of the two-year school budget in 2011. (School districts made up some of that by saving on employee benefits and retirement plans.) The state’s inflation-adjusted school spending budget fell by 20 percent from the previous decade’s peak and has not recovered.

Democrats knew the issue would be potent, because localities across Wisconsin tried to compensate for the state’s pullback with scores of bond referenda to raise money in school districts from rural Wisconsin to the Milwaukee suburbs. More than 60 districts had more than $1.4 billion in spending on the ballot on Tuesday, part of a record wave. With the state’s economy going strong, voters’ views on taxes and spending have done an about-face since 2013: They’re ready to pay more for education.

But the piecemeal fix comes with consequences. The rise of localized spending measures (tied to property taxes) is exacerbating inequality between rich and poor districts. As is the state’s Act 10–driven teacher shortage, which has given big-spending districts an advantage in the newly fluid labor market. The achievement gap between black and white students graduating high school in Wisconsin is the highest in the nation. Research from the Center for American Progress suggests that Act 10 did lasting harm to the state’s teachers; a study by the economist E. Jason Baron reports that student test scores fell as a result. Act 10 did save taxpayers money—by taking it out of teachers’ pockets.

That correlation aside, the backlash against Walker is barely about Act 10’s attacks on labor. In fact, Democrats may find Walker’s signature bill impossible to undo, especially since Republicans continue to thrive in Wisconsin statehouse elections. It might not be that easy to put the unions—and the aspirational, middle-class jobs they created—back together again.

Ironically, Walker’s other big legacy in Wisconsin may be the Foxconn plant, for which the state is dedicating the largest subsidy for a foreign company in U.S. history. Even if the deal went perfectly as planned, it would still amount to a gigantic state investment to create a bunch of good middle-class jobs. Which, if you think about it, is kind of what Wisconsin once had in its public-sector unions. Paying for teachers’ health care will probably have been cheaper, per job, than what the state seems likely to shell out for Foxconn’s new workforce. But maybe the more important difference is in the types of employees the state is supporting. The old ones taught children; the new ones will build LCD screens.